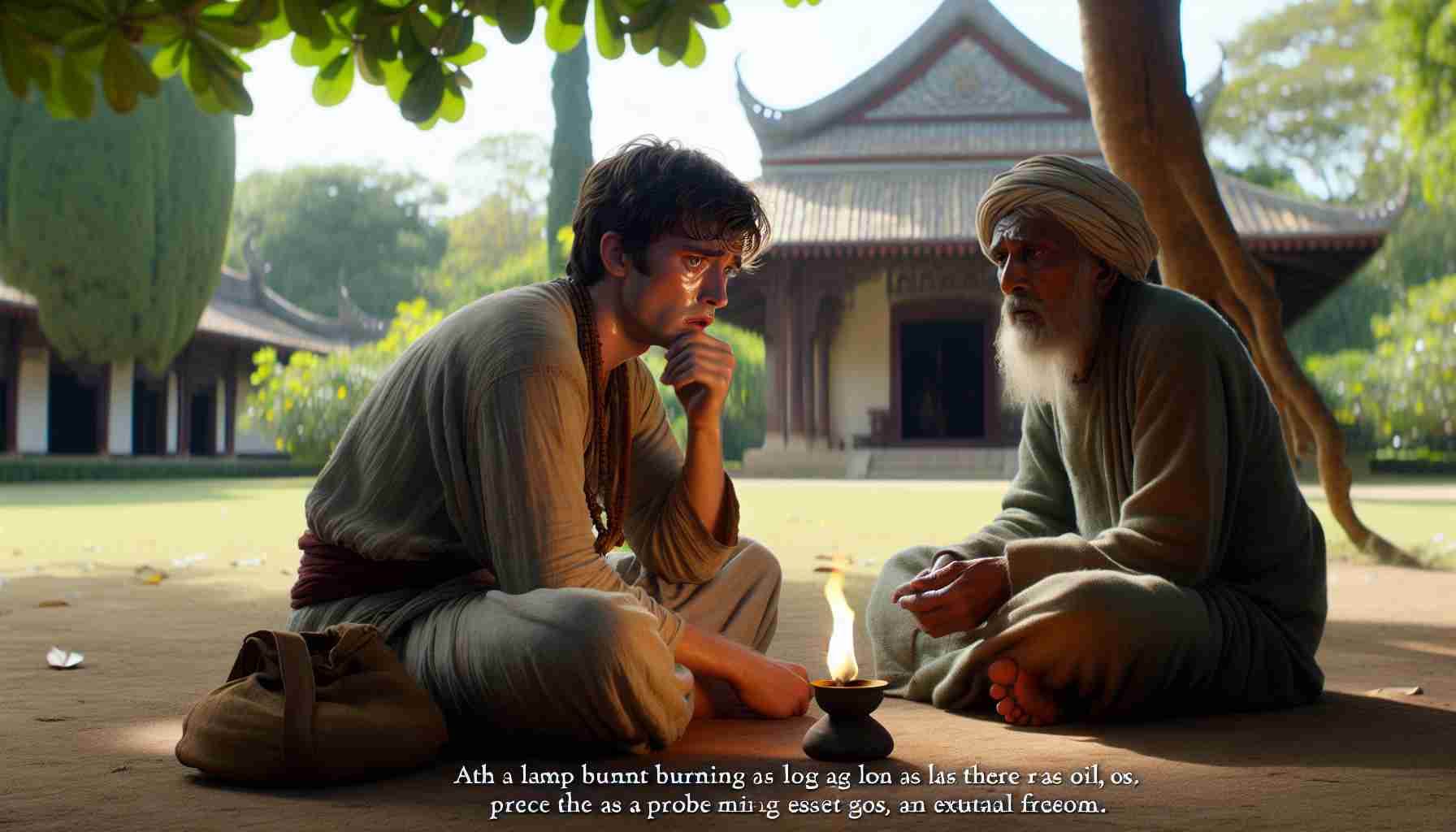

The sun had not fully risen the morning I wandered into the garden at Jetavana Monastery, golden light barely brushing the tops of the trees. My name is Ananda, and for years I had served as the personal attendant and devoted cousin of Siddhartha Gautama—the one people called the Buddha, the Enlightened One. I had followed him for many seasons, listening, learning, remembering every word he said like pearls on a thread. But that day, beneath the whispering trees, I wasn’t reciting teachings or greeting monks. I was weeping.

You see, I had heard the whispers among the Sangha—the community of monks—that the Blessed One’s health was failing. Though he had never clung to the body nor feared death, I could not imagine this world without his footsteps echoing on monastery paths.

The garden was quiet. The leaves danced softly in the breeze, and I sat alone on a stone bench, aching with sorrow. That’s when his gentle voice broke the stillness.

“Ananda,” he said, standing behind me with hands folded calmly. His eyes, still bright though his body had grown thin, watched me with the same kindness he always had.

I bowed deeply, hiding my tears. “Blessed One, they say… they say you are leaving us soon.” I said the words shakily.

He sat beside me. “All things that arise must also pass away, Ananda. Have I not taught you this again and again?”

“Yes, you have, Lord,” I whispered. “But I still feel this pain… this fear. I don’t know how to let go.”

He was quiet for a while, watching the petals fall from a blooming tree. “Do you remember teaching the monks about the lamp, Ananda?”

I frowned, thinking hard. “Yes, Lord. That a lamp continues to shine as long as there is oil… but when the oil is gone, the flame goes out.”

He nodded. “The body is like that lamp. As long as the causes and conditions support it, it endures. But when those conditions disappear, it is only natural for the flame to go out. I do not grieve that the lamp goes out. I am at peace with the nature of all things.”

“But I am not,” I admitted. “How do I come to peace, Lord?”

He placed his hand on mine. “Through mindfulness, Ananda. Watch your sorrow as it rises. See it fully. Do not push it away or cling to it as yours. Let it be like a passing cloud. When you see clearly that even sadness is not permanent, you will understand.”

Tears fell again, but this time my heart was quiet. Somehow, in his words, I began to feel something new—not detachment like walking away, but freedom. Freedom from needing things to stay the same.

That was the silent turning point.

I thought love meant holding on—but the Buddha showed me that real love listens, sees, and releases. After that talk, I followed him more mindfully, cherishing each step, not as something to keep, but as something to witness with gratitude.

And when the Blessed One finally passed into Parinirvana, I did weep. But I also sat still, breathing in the impermanence he had taught me to see. I was no longer just the Buddha’s attendant. I was his student—awake enough, at last, to let go.

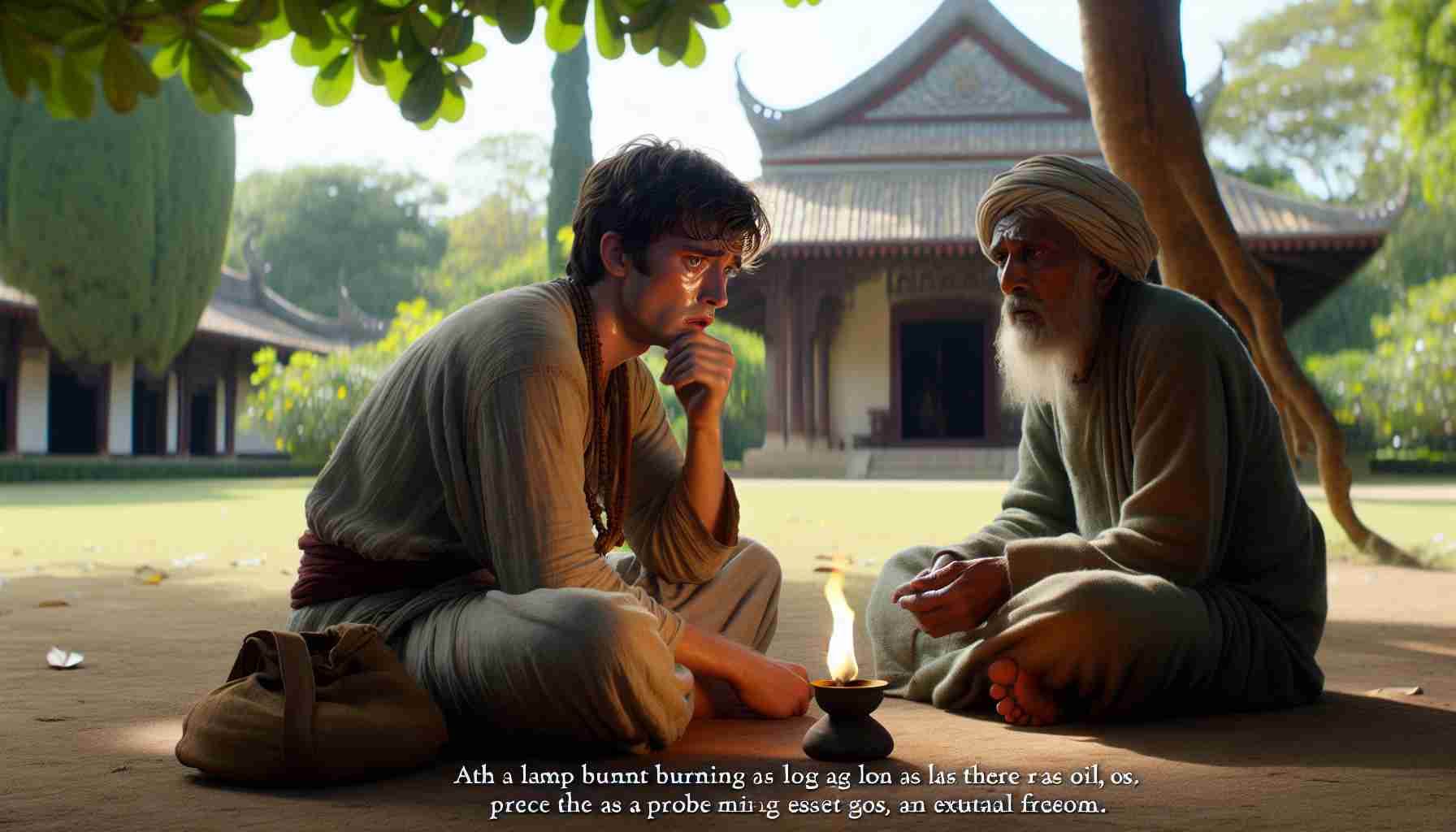

The sun had not fully risen the morning I wandered into the garden at Jetavana Monastery, golden light barely brushing the tops of the trees. My name is Ananda, and for years I had served as the personal attendant and devoted cousin of Siddhartha Gautama—the one people called the Buddha, the Enlightened One. I had followed him for many seasons, listening, learning, remembering every word he said like pearls on a thread. But that day, beneath the whispering trees, I wasn’t reciting teachings or greeting monks. I was weeping.

You see, I had heard the whispers among the Sangha—the community of monks—that the Blessed One’s health was failing. Though he had never clung to the body nor feared death, I could not imagine this world without his footsteps echoing on monastery paths.

The garden was quiet. The leaves danced softly in the breeze, and I sat alone on a stone bench, aching with sorrow. That’s when his gentle voice broke the stillness.

“Ananda,” he said, standing behind me with hands folded calmly. His eyes, still bright though his body had grown thin, watched me with the same kindness he always had.

I bowed deeply, hiding my tears. “Blessed One, they say… they say you are leaving us soon.” I said the words shakily.

He sat beside me. “All things that arise must also pass away, Ananda. Have I not taught you this again and again?”

“Yes, you have, Lord,” I whispered. “But I still feel this pain… this fear. I don’t know how to let go.”

He was quiet for a while, watching the petals fall from a blooming tree. “Do you remember teaching the monks about the lamp, Ananda?”

I frowned, thinking hard. “Yes, Lord. That a lamp continues to shine as long as there is oil… but when the oil is gone, the flame goes out.”

He nodded. “The body is like that lamp. As long as the causes and conditions support it, it endures. But when those conditions disappear, it is only natural for the flame to go out. I do not grieve that the lamp goes out. I am at peace with the nature of all things.”

“But I am not,” I admitted. “How do I come to peace, Lord?”

He placed his hand on mine. “Through mindfulness, Ananda. Watch your sorrow as it rises. See it fully. Do not push it away or cling to it as yours. Let it be like a passing cloud. When you see clearly that even sadness is not permanent, you will understand.”

Tears fell again, but this time my heart was quiet. Somehow, in his words, I began to feel something new—not detachment like walking away, but freedom. Freedom from needing things to stay the same.

That was the silent turning point.

I thought love meant holding on—but the Buddha showed me that real love listens, sees, and releases. After that talk, I followed him more mindfully, cherishing each step, not as something to keep, but as something to witness with gratitude.

And when the Blessed One finally passed into Parinirvana, I did weep. But I also sat still, breathing in the impermanence he had taught me to see. I was no longer just the Buddha’s attendant. I was his student—awake enough, at last, to let go.