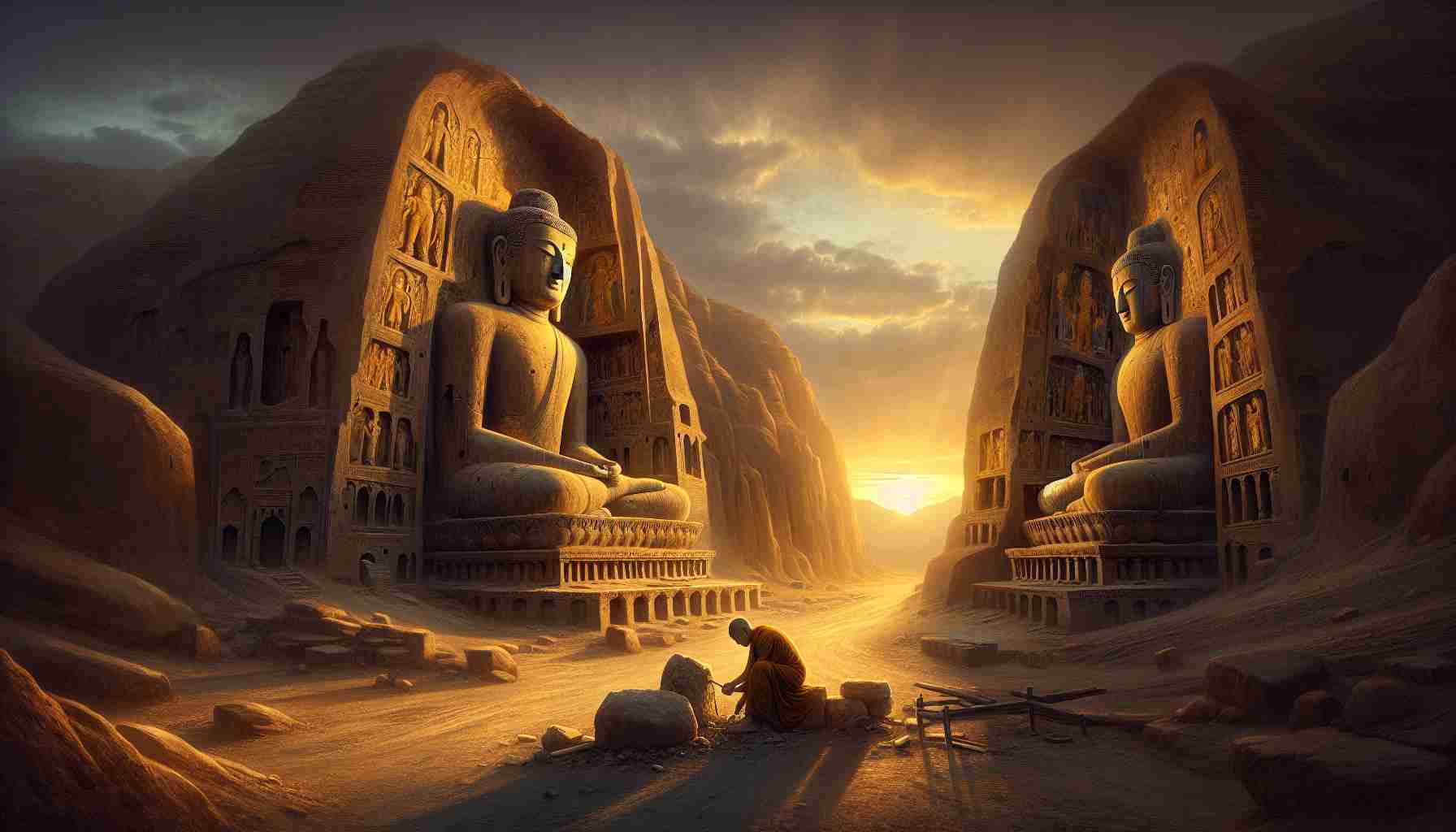

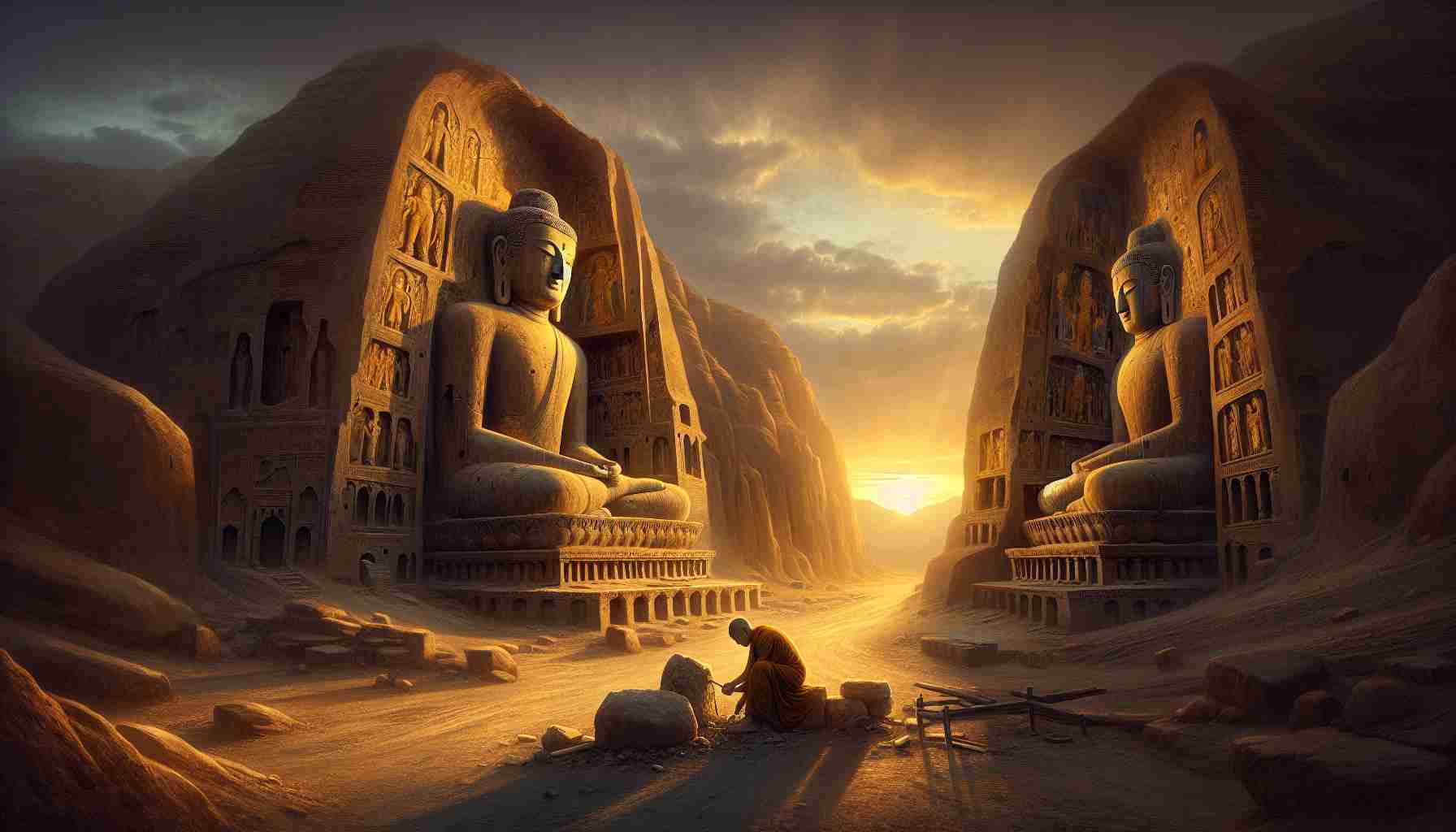

The monk’s fingers, dusty with stone, trembled against the cave wall. Year after year, he had returned to this very ledge of the Bamiyan Valley, where the cliffs loomed like ancient scrolls, silent but waiting to speak. Today, he would carve the final stanza of the Lotus Sutra, his chisel whispering truths into stone.

Above him towered the immense statue of the Buddha, forty-five meters tall, its robes draped in the delicate folds of compassion, its gaze softened by time and smoke. The monument was more than stone. It was sermon and sanctuary, creation and creator. For generations, monks like him had chiseled enlightenment into the cliffs of Afghanistan, believing that permanence was best found in the solid hush of earth.

In the third century CE, pilgrims had climbed these cliffs in search of wisdom. They found it etched in the rock—in niches adorned with murals of golden Bodhisattvas and heavenly realms, in scripture painted with mineral dyes and prayers embedded in the very brushstrokes. The valley was a sacred artery along the Silk Road; a hush of contemplation nestled between caravans and kingdoms, where traders bartered silk and spices beneath the gaze of serenity carved from limestone.

But time, even when resisted in stone, leaves its mark.

By the ninth century, winds of change swept the land. Islam had entered the region, and the last Buddhist monasteries shuttered their wooden doors. The statues, too large to be destroyed and too holy to be ignored, were left standing—monolithic vaults of forgotten sermons. Dust settled into the folds of the Buddha’s cloak, bats nested behind its brows, and the paintings faded like old dreams.

Centuries passed.

In 632, the Chinese monk Xuanzang recorded the splendor of the statues in his pilgrimage journals: “two standing Buddhas... glittering with precious gold.” Kings heeded his words, seeking the valley’s wonders, but found only silence and broken paths. Legends bloomed nonetheless. Some swore the statues bled when struck. Others believed a hidden city throbbed beneath the cliffs. In winter, shepherds heard chants wafting from the niches, whispered in languages no longer spoken.

Then came March of 2001.

The sky wept dust as explosions cracked across Bamiyan. The Taliban, fueled by a fervor to erase history, felled the statues with dynamite. Men chanted as stone hearts buckled under fire. Centuries of devotion dissolved in smoke. Where once stood the sentinels of compassion, there now yawned voids—the absence itself a howl of grief.

But stone remembers.

In the months that followed, archaeologists picked through the rubble like mourners gathering relics from a grave. Hidden tunnels emerged behind where the statues had stood—winding catacombs painted with celestial maps, mandalas swimming in ochre and lapis lazuli. In a hollowness carved for stillness, color shimmered in the dark, untouched by the violence above.

Within one such chamber, buried behind centuries of collapse, they found a mural of Buddha descending from heaven, surrounded by robes that once shimmered with gold leaf. The fresco, dated to the fifth century, revealed a mystery: it was painted using oil-based techniques, a method known in China centuries later, but attributed nowhere else in this region or time. Who brought it here? Why did they vanish?

Theories flowed. Some claimed fleeing artists from Gandhara brought their secrets west. Others insisted it was spontaneous genius birthed in isolation. But the monks had left no answers—only beauty that outlived them.

In time, the niches that once cradled the Buddhas did not remain empty. At dusk, when the wind curled through the valley, the cliffside caught fire with projection. A German artist, taking up the mantle of memory, cast light into the void—3D replicas of the Buddhas, shimmering in silence, phantoms of a faith once carved into permanence.

Locals gathered. Elders wept. Children raised smartphones to capture ghosts of stone. The Bamiyan Buddhas had returned, not in form, but in echo.

Some say that to carve into stone is to defy the ravages of time. But here, in a valley once cloaked in chants and saffron robes, the truth lay deeper. The monks of Bamiyan had not simply carved to preserve—they carved to be forgotten and rediscovered. They etched their teachings into silence, trusting the cliffs to one day speak again.

And they did.

The monk’s fingers, dusty with stone, trembled against the cave wall. Year after year, he had returned to this very ledge of the Bamiyan Valley, where the cliffs loomed like ancient scrolls, silent but waiting to speak. Today, he would carve the final stanza of the Lotus Sutra, his chisel whispering truths into stone.

Above him towered the immense statue of the Buddha, forty-five meters tall, its robes draped in the delicate folds of compassion, its gaze softened by time and smoke. The monument was more than stone. It was sermon and sanctuary, creation and creator. For generations, monks like him had chiseled enlightenment into the cliffs of Afghanistan, believing that permanence was best found in the solid hush of earth.

In the third century CE, pilgrims had climbed these cliffs in search of wisdom. They found it etched in the rock—in niches adorned with murals of golden Bodhisattvas and heavenly realms, in scripture painted with mineral dyes and prayers embedded in the very brushstrokes. The valley was a sacred artery along the Silk Road; a hush of contemplation nestled between caravans and kingdoms, where traders bartered silk and spices beneath the gaze of serenity carved from limestone.

But time, even when resisted in stone, leaves its mark.

By the ninth century, winds of change swept the land. Islam had entered the region, and the last Buddhist monasteries shuttered their wooden doors. The statues, too large to be destroyed and too holy to be ignored, were left standing—monolithic vaults of forgotten sermons. Dust settled into the folds of the Buddha’s cloak, bats nested behind its brows, and the paintings faded like old dreams.

Centuries passed.

In 632, the Chinese monk Xuanzang recorded the splendor of the statues in his pilgrimage journals: “two standing Buddhas... glittering with precious gold.” Kings heeded his words, seeking the valley’s wonders, but found only silence and broken paths. Legends bloomed nonetheless. Some swore the statues bled when struck. Others believed a hidden city throbbed beneath the cliffs. In winter, shepherds heard chants wafting from the niches, whispered in languages no longer spoken.

Then came March of 2001.

The sky wept dust as explosions cracked across Bamiyan. The Taliban, fueled by a fervor to erase history, felled the statues with dynamite. Men chanted as stone hearts buckled under fire. Centuries of devotion dissolved in smoke. Where once stood the sentinels of compassion, there now yawned voids—the absence itself a howl of grief.

But stone remembers.

In the months that followed, archaeologists picked through the rubble like mourners gathering relics from a grave. Hidden tunnels emerged behind where the statues had stood—winding catacombs painted with celestial maps, mandalas swimming in ochre and lapis lazuli. In a hollowness carved for stillness, color shimmered in the dark, untouched by the violence above.

Within one such chamber, buried behind centuries of collapse, they found a mural of Buddha descending from heaven, surrounded by robes that once shimmered with gold leaf. The fresco, dated to the fifth century, revealed a mystery: it was painted using oil-based techniques, a method known in China centuries later, but attributed nowhere else in this region or time. Who brought it here? Why did they vanish?

Theories flowed. Some claimed fleeing artists from Gandhara brought their secrets west. Others insisted it was spontaneous genius birthed in isolation. But the monks had left no answers—only beauty that outlived them.

In time, the niches that once cradled the Buddhas did not remain empty. At dusk, when the wind curled through the valley, the cliffside caught fire with projection. A German artist, taking up the mantle of memory, cast light into the void—3D replicas of the Buddhas, shimmering in silence, phantoms of a faith once carved into permanence.

Locals gathered. Elders wept. Children raised smartphones to capture ghosts of stone. The Bamiyan Buddhas had returned, not in form, but in echo.

Some say that to carve into stone is to defy the ravages of time. But here, in a valley once cloaked in chants and saffron robes, the truth lay deeper. The monks of Bamiyan had not simply carved to preserve—they carved to be forgotten and rediscovered. They etched their teachings into silence, trusting the cliffs to one day speak again.

And they did.