The morning breeze was soft, like a whisper brushing my cheek. I was walking along the garden path behind the temple, my hands clutching a scroll I didn’t understand. I had stayed awake all night trying to read it. The words were so quiet, so light, and I wanted to grasp their meaning. But the more I tried, the more confused I became.

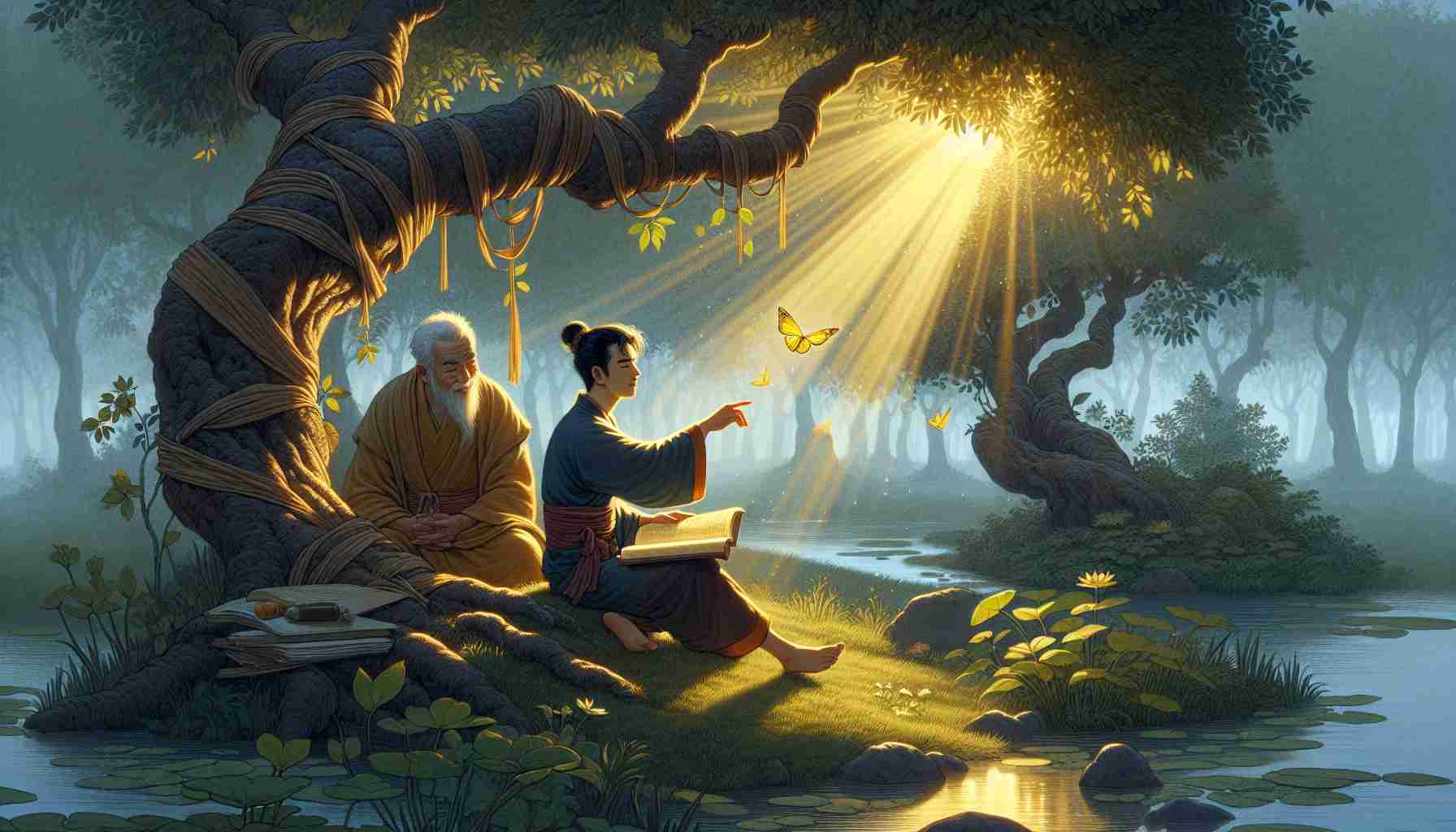

I was just a young student then, living at Master Zhuangzi’s school—a wise and kind old man who loved to tell stories more than give direct answers. That day, he found me under a tree with a frustrated look and parchment spread out beside me.

“You look like you wrestled a dragon,” he said, chuckling.

“I don’t understand, Master,” I frowned. “You said the Tao is the Way—flowing and peaceful. But this scroll warns: ‘He who stands on tiptoe does not stand firm. He who rushes ahead does not go far.’ Doesn’t hard work matter?”

He smiled and sat beside me, watching the leaves drift from the tree above.

“Do you see that butterfly?” he asked.

I turned my head. A small yellow butterfly wobbled through the air.

“She doesn’t flap hard or push the wind,” Zhuangzi said. “She floats. She rests. She lets the wind carry her. She obeys what's already happening.”

I blinked. “But she’s still moving.”

“Yes,” he said, “but without forcing. That’s called Wu Wei—action without strain. It doesn’t mean doing nothing. It means doing only what needs to be done, gently, wisely, and in harmony with what already is.”

I sat back and watched the butterfly dance across the garden. Every time the wind shifted, she changed with it—not fighting, just following.

“But,” I said slowly, “don’t we need to try harder to be better?”

“Sometimes,” Zhuangzi nodded. “But trying too hard is like standing on your tiptoes to look taller. You may rise for a moment, but you’ll soon fall. The Tao is simple. Just be who you are, not who you think you should be.”

Later that evening, I walked by the pond. I noticed how naturally the water held the reflection of the moon—without effort. That’s when something inside me softened. Maybe I didn’t need to struggle to understand everything at once. Maybe the Tao was something I could feel, not grab.

That night, I rolled up the scroll and placed it beside me. I didn’t read it. I just listened to the gentle wind outside and felt peaceful for the first time in days.

I didn’t change overnight. But now, whenever I feel like rushing ahead in life, I remember the butterfly. I try not to push. I let the wind carry me—trusting the Way, learning to float instead of fly too fast.

And in that, I found freedom.

The morning breeze was soft, like a whisper brushing my cheek. I was walking along the garden path behind the temple, my hands clutching a scroll I didn’t understand. I had stayed awake all night trying to read it. The words were so quiet, so light, and I wanted to grasp their meaning. But the more I tried, the more confused I became.

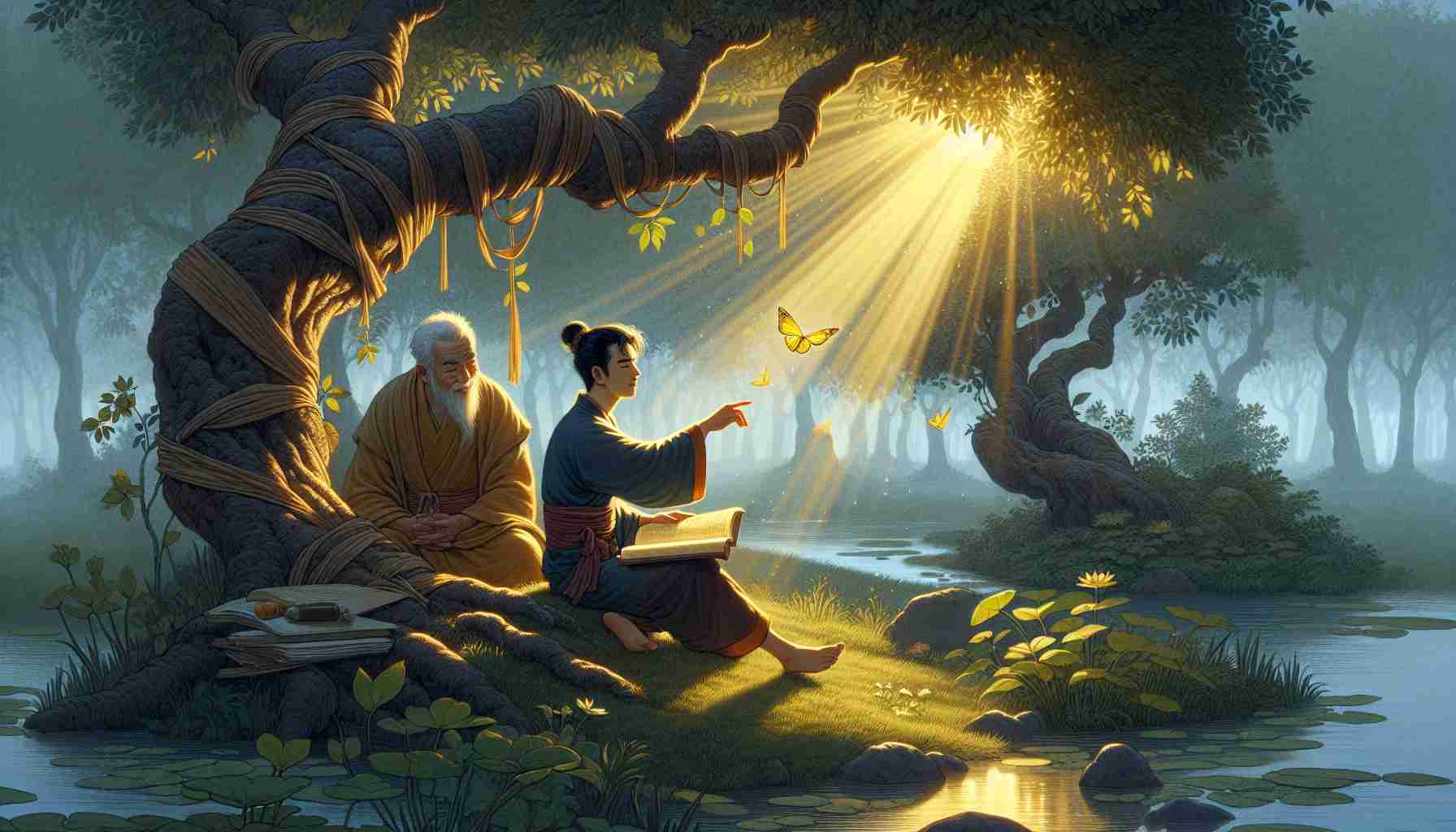

I was just a young student then, living at Master Zhuangzi’s school—a wise and kind old man who loved to tell stories more than give direct answers. That day, he found me under a tree with a frustrated look and parchment spread out beside me.

“You look like you wrestled a dragon,” he said, chuckling.

“I don’t understand, Master,” I frowned. “You said the Tao is the Way—flowing and peaceful. But this scroll warns: ‘He who stands on tiptoe does not stand firm. He who rushes ahead does not go far.’ Doesn’t hard work matter?”

He smiled and sat beside me, watching the leaves drift from the tree above.

“Do you see that butterfly?” he asked.

I turned my head. A small yellow butterfly wobbled through the air.

“She doesn’t flap hard or push the wind,” Zhuangzi said. “She floats. She rests. She lets the wind carry her. She obeys what's already happening.”

I blinked. “But she’s still moving.”

“Yes,” he said, “but without forcing. That’s called Wu Wei—action without strain. It doesn’t mean doing nothing. It means doing only what needs to be done, gently, wisely, and in harmony with what already is.”

I sat back and watched the butterfly dance across the garden. Every time the wind shifted, she changed with it—not fighting, just following.

“But,” I said slowly, “don’t we need to try harder to be better?”

“Sometimes,” Zhuangzi nodded. “But trying too hard is like standing on your tiptoes to look taller. You may rise for a moment, but you’ll soon fall. The Tao is simple. Just be who you are, not who you think you should be.”

Later that evening, I walked by the pond. I noticed how naturally the water held the reflection of the moon—without effort. That’s when something inside me softened. Maybe I didn’t need to struggle to understand everything at once. Maybe the Tao was something I could feel, not grab.

That night, I rolled up the scroll and placed it beside me. I didn’t read it. I just listened to the gentle wind outside and felt peaceful for the first time in days.

I didn’t change overnight. But now, whenever I feel like rushing ahead in life, I remember the butterfly. I try not to push. I let the wind carry me—trusting the Way, learning to float instead of fly too fast.

And in that, I found freedom.