I was eleven when the prophet Yonah—also known as Jonah—came through our town, his face pale and his eyes always shifting, like a man being chased by something only he could see. I wasn’t a prophet, just a fisherman’s son from a quiet village near the sea. But I remember that day like it was etched on my skin.

My father had gone down to the docks to mend nets, and I tagged along, hoping to sail before the sun reached its peak. That’s when I saw him—Yonah, son of Amittai, the prophet who once delivered blessings to the king. But this time, he looked nothing like a man with good news.

He paid for passage on a ship headed far away, to Tarshish—so far it was practically the edge of the world. I asked my father, “Why would a prophet sail away from Yisrael—Israel?” He frowned. “Only one reason,” he said. “He must be running from Hashem—the name we use to speak of God with reverence.”

That stayed with me. Who runs from Hashem?

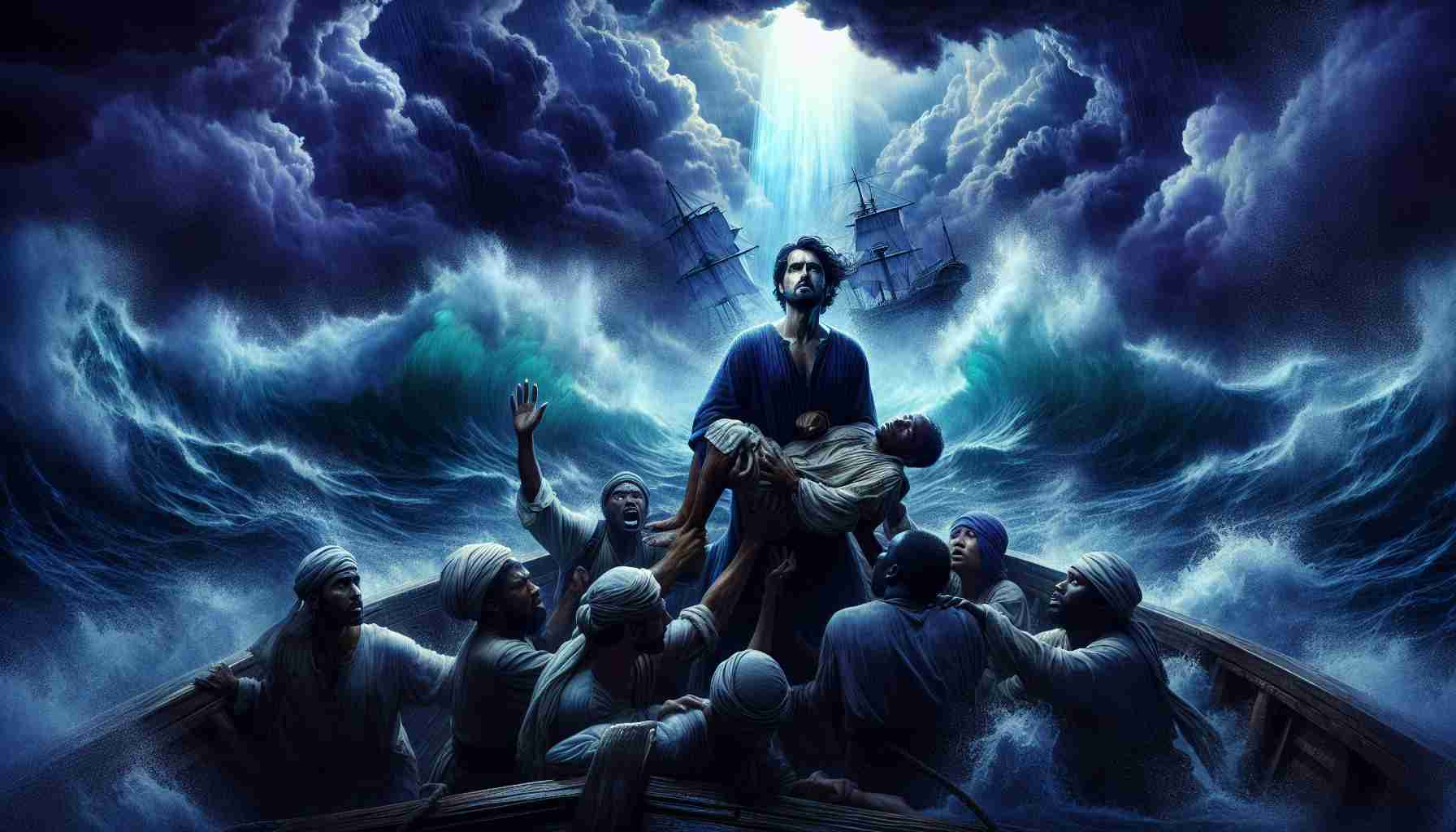

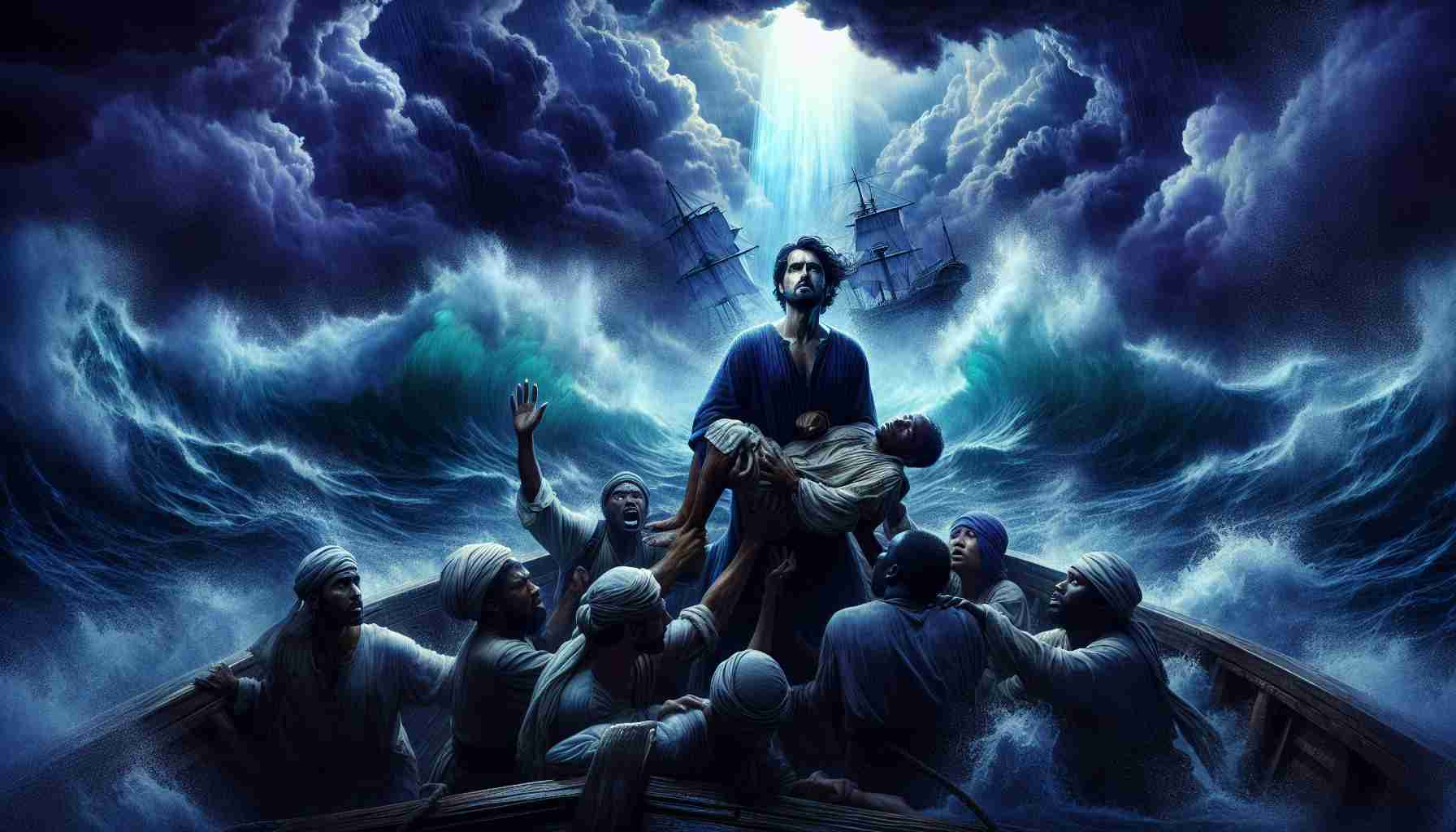

Days later, word spread like a sandstorm: Yonah’s ship had been caught in a great storm. Sailors threw cargo overboard. They even cast lots—tiny stones marked with names—to see who brought trouble aboard. The lot fell to Yonah.

I later heard the rest from a merchant who’d been in the harbor. “Yonah told them he feared Hashem,” the man whispered, “the God of the heavens, who made the sea. He begged to be thrown into the water to save them.” He shrugged. “What kind of man asks to drown?”

I couldn’t stop wondering. Why not just go to Nineveh like he was told? Why run? Why choose the sea instead of obedience?

But then came the strangest part of the tale.

“He didn’t die,” a sailor told someone in the market. “A great fish swallowed him whole.”

I gasped. “And he lived?”

“For three days and nights,” the man said. “Inside the belly of the beast, he prayed. Cried out to Hashem. Promised to do what he was told from the beginning.”

I thought about that for weeks. I’d never been in a fish's belly, but I had been stubborn. I remembered the time I disobeyed my father, hiding when he called, ashamed of a broken net. I was afraid of punishment—but more afraid of disappointing him. It took only minutes before I came out crying, asking to be forgiven. Yonah needed three whole days.

The Torah teaches us that Hashem gave us a Brit—a holy covenant. We aren’t just His people when we behave. We are still His even when we flee. Even when we fail.

In the belly of the fish, Yonah remembered. He promised worship. He returned to the covenant. That’s what we call Teshuvah—returning to Hashem after we’ve done wrong.

I never saw Yonah again, but I heard he finally went to Nineveh—and the people listened. A whole city changed because one man remembered who he was in the deepest place of all.

Sometimes mercy waits in unexpected places—even in the belly of a fish.

I was eleven when the prophet Yonah—also known as Jonah—came through our town, his face pale and his eyes always shifting, like a man being chased by something only he could see. I wasn’t a prophet, just a fisherman’s son from a quiet village near the sea. But I remember that day like it was etched on my skin.

My father had gone down to the docks to mend nets, and I tagged along, hoping to sail before the sun reached its peak. That’s when I saw him—Yonah, son of Amittai, the prophet who once delivered blessings to the king. But this time, he looked nothing like a man with good news.

He paid for passage on a ship headed far away, to Tarshish—so far it was practically the edge of the world. I asked my father, “Why would a prophet sail away from Yisrael—Israel?” He frowned. “Only one reason,” he said. “He must be running from Hashem—the name we use to speak of God with reverence.”

That stayed with me. Who runs from Hashem?

Days later, word spread like a sandstorm: Yonah’s ship had been caught in a great storm. Sailors threw cargo overboard. They even cast lots—tiny stones marked with names—to see who brought trouble aboard. The lot fell to Yonah.

I later heard the rest from a merchant who’d been in the harbor. “Yonah told them he feared Hashem,” the man whispered, “the God of the heavens, who made the sea. He begged to be thrown into the water to save them.” He shrugged. “What kind of man asks to drown?”

I couldn’t stop wondering. Why not just go to Nineveh like he was told? Why run? Why choose the sea instead of obedience?

But then came the strangest part of the tale.

“He didn’t die,” a sailor told someone in the market. “A great fish swallowed him whole.”

I gasped. “And he lived?”

“For three days and nights,” the man said. “Inside the belly of the beast, he prayed. Cried out to Hashem. Promised to do what he was told from the beginning.”

I thought about that for weeks. I’d never been in a fish's belly, but I had been stubborn. I remembered the time I disobeyed my father, hiding when he called, ashamed of a broken net. I was afraid of punishment—but more afraid of disappointing him. It took only minutes before I came out crying, asking to be forgiven. Yonah needed three whole days.

The Torah teaches us that Hashem gave us a Brit—a holy covenant. We aren’t just His people when we behave. We are still His even when we flee. Even when we fail.

In the belly of the fish, Yonah remembered. He promised worship. He returned to the covenant. That’s what we call Teshuvah—returning to Hashem after we’ve done wrong.

I never saw Yonah again, but I heard he finally went to Nineveh—and the people listened. A whole city changed because one man remembered who he was in the deepest place of all.

Sometimes mercy waits in unexpected places—even in the belly of a fish.