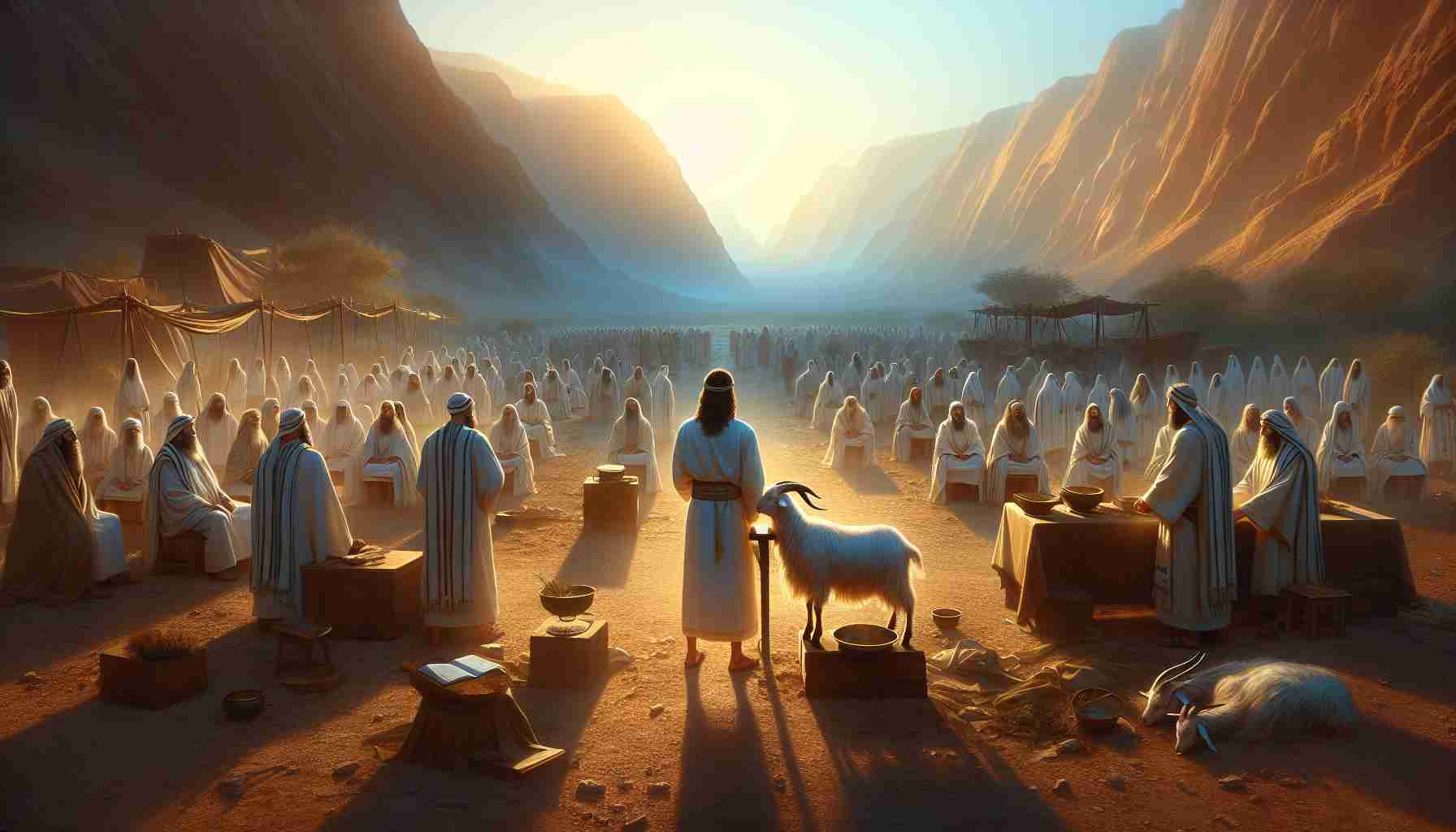

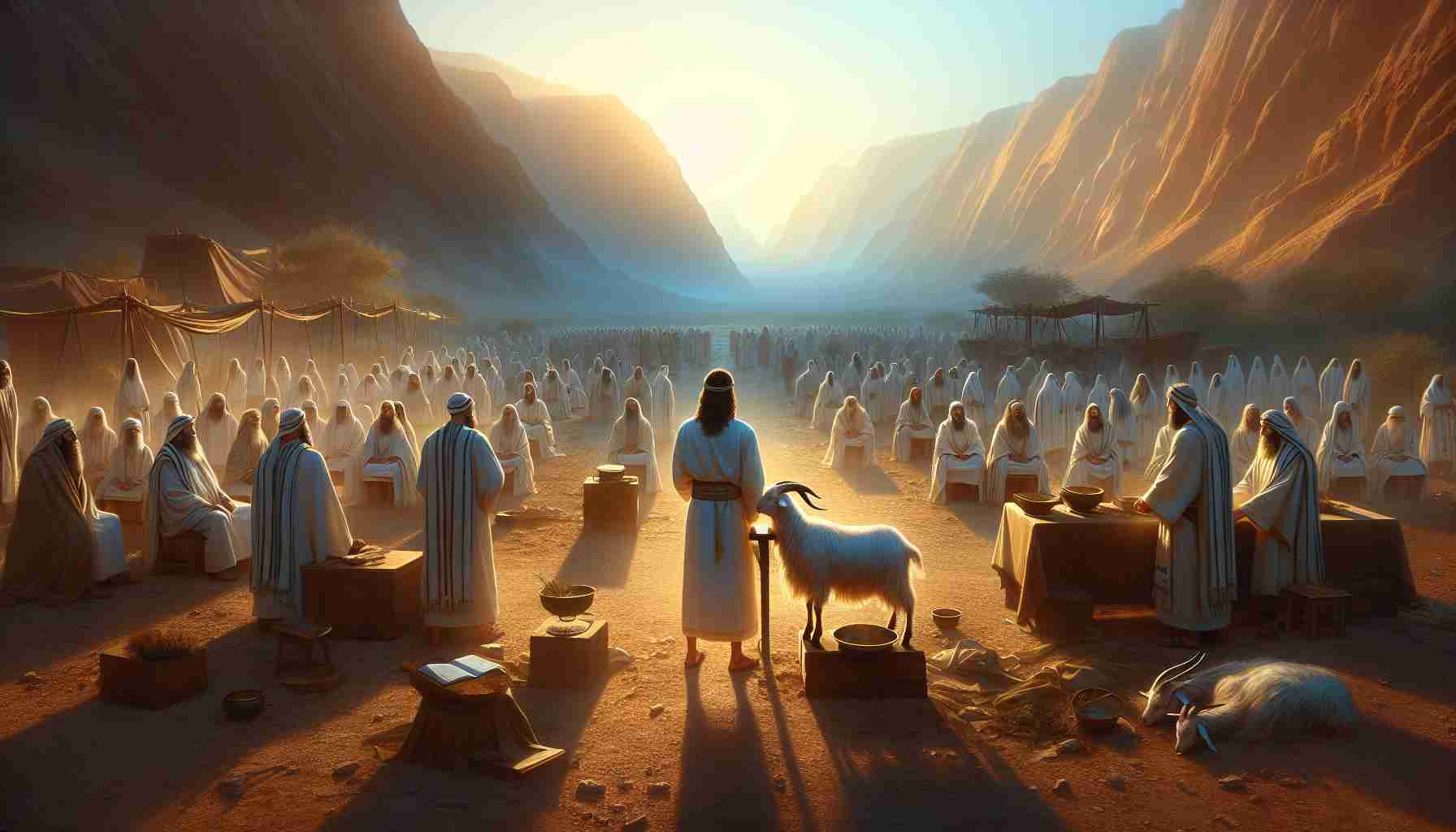

I wasn’t a priest. I wasn’t a Levite. I was just a laborer, the kind who hauled stones and built tents, sweating through the heat of the desert sun. Yet on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, I stood among my people in silence, watching the High Priest—the kohen gadol—move through the sacred rituals, my heart pounding like a drum.

It was the scapegoat that made my chest tighten every year.

I never carried the goat myself, but I knew the man who did. His name was Malachai, and we’d traveled together from Egypt to Mount Sinai, through thick and thin and the endless wandering. He had been chosen, more than once, for the task. To lead the goat—the one on whom the High Priest laid the sins of all Israel—out into the wilderness and release it alive, far away from camp.

He told me what it felt like.

“It’s not just an animal,” he’d once said, his voice low and rough as dried reeds. “You feel the weight of those sins, as if they press on your back. Guilt you didn’t commit, shame you didn’t earn. And still, somehow, they become yours to carry.”

This year, he was too old. His son, Levi, would go instead.

I stood next to Malachai as the goats were brought forward—two of them, nearly identical. One was for God, offered as a sin offering on the altar. The other… the scapegoat. The High Priest drew lots, as the Torah commanded in Vayikra, also known as Leviticus, chapter 16.

Levi stepped forward when called. The goat twisted its head, as if it knew the burden to come. The crowd murmured prayers, heads bowed low. My own lips moved, dry and cracked.

When the High Priest placed both hands on the animal’s head and confessed the sins of the entire nation, I felt something in me break. I thought of my temper. Of moments I hadn’t trusted God, even after all He had done for us—splitting the sea, feeding us manna, giving us His laws.

I had sinned. And now… now my wrongs stood on the back of that goat.

Levi took the rope and led it east, toward the hills, toward the rocky silence where no man lived. No one spoke. We watched until they both vanished from sight.

Malachai placed a hand on my shoulder. “We’re free,” he whispered. “Not by our own hands… but by His mercy.”

I didn’t feel light right away. The guilt didn’t vanish in an instant. But I looked up—at the sky that stretched forever—and I knew I had been given a second chance.

Yom Kippur wasn’t just about forgiveness. It was about starting again.

And though I had not led the goat myself, I too had placed my burdens upon it. And in that moment, in that silence, I believed—deeply—that God had heard.

I wasn’t a priest. I wasn’t a Levite. I was just a laborer, the kind who hauled stones and built tents, sweating through the heat of the desert sun. Yet on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, I stood among my people in silence, watching the High Priest—the kohen gadol—move through the sacred rituals, my heart pounding like a drum.

It was the scapegoat that made my chest tighten every year.

I never carried the goat myself, but I knew the man who did. His name was Malachai, and we’d traveled together from Egypt to Mount Sinai, through thick and thin and the endless wandering. He had been chosen, more than once, for the task. To lead the goat—the one on whom the High Priest laid the sins of all Israel—out into the wilderness and release it alive, far away from camp.

He told me what it felt like.

“It’s not just an animal,” he’d once said, his voice low and rough as dried reeds. “You feel the weight of those sins, as if they press on your back. Guilt you didn’t commit, shame you didn’t earn. And still, somehow, they become yours to carry.”

This year, he was too old. His son, Levi, would go instead.

I stood next to Malachai as the goats were brought forward—two of them, nearly identical. One was for God, offered as a sin offering on the altar. The other… the scapegoat. The High Priest drew lots, as the Torah commanded in Vayikra, also known as Leviticus, chapter 16.

Levi stepped forward when called. The goat twisted its head, as if it knew the burden to come. The crowd murmured prayers, heads bowed low. My own lips moved, dry and cracked.

When the High Priest placed both hands on the animal’s head and confessed the sins of the entire nation, I felt something in me break. I thought of my temper. Of moments I hadn’t trusted God, even after all He had done for us—splitting the sea, feeding us manna, giving us His laws.

I had sinned. And now… now my wrongs stood on the back of that goat.

Levi took the rope and led it east, toward the hills, toward the rocky silence where no man lived. No one spoke. We watched until they both vanished from sight.

Malachai placed a hand on my shoulder. “We’re free,” he whispered. “Not by our own hands… but by His mercy.”

I didn’t feel light right away. The guilt didn’t vanish in an instant. But I looked up—at the sky that stretched forever—and I knew I had been given a second chance.

Yom Kippur wasn’t just about forgiveness. It was about starting again.

And though I had not led the goat myself, I too had placed my burdens upon it. And in that moment, in that silence, I believed—deeply—that God had heard.