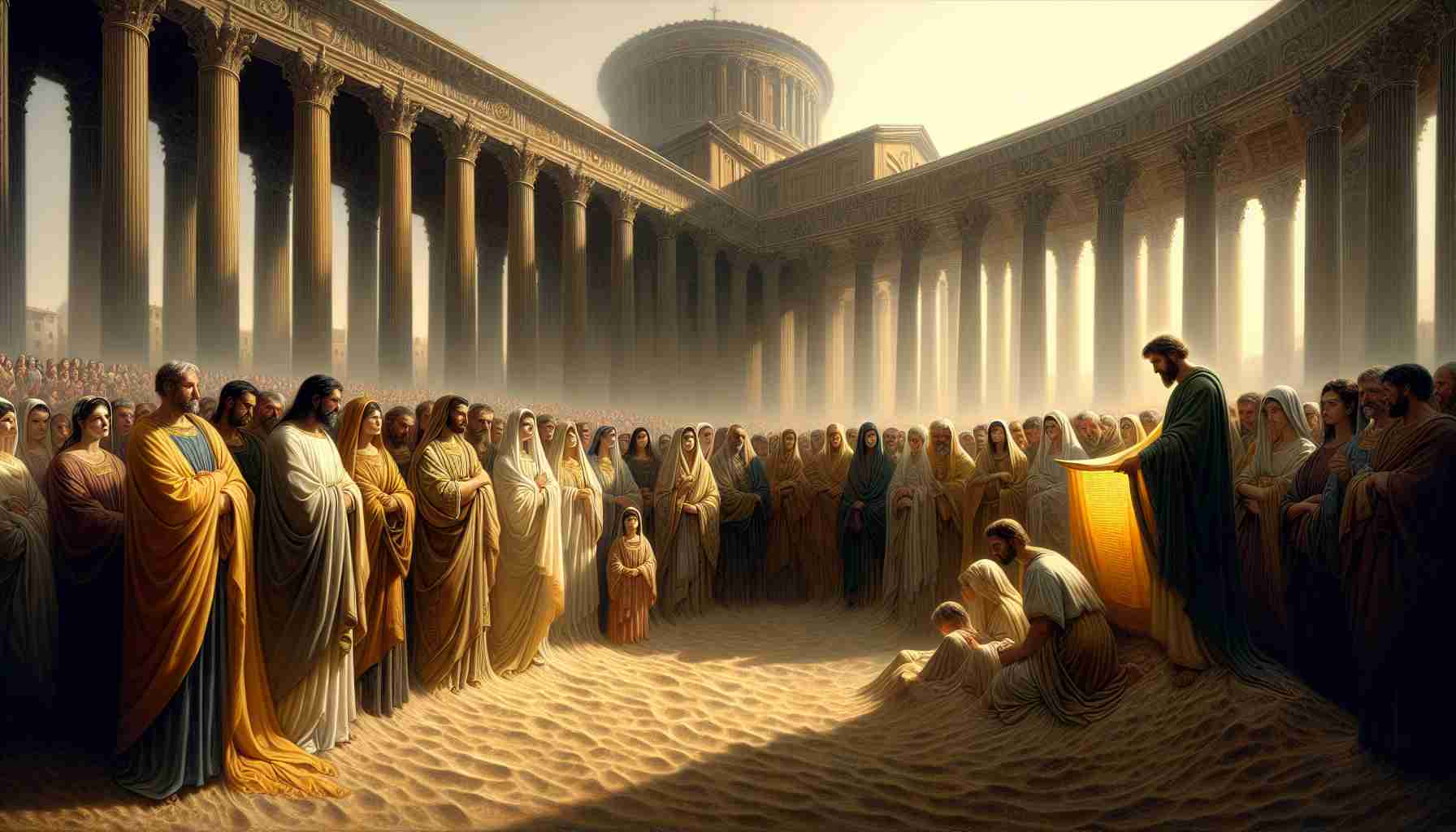

The air over the Roman proconsul’s tribunal shimmered in the July heat, but no earthly glare could match the fire in Speratus’s eyes. He stood tall among eleven others—ten men and two women—his robes still marked with dust from the long walk to Carthage. Behind him loomed the basilica’s colonnades, their solemn marble carving a line of shadow across the noon-lit sand. The crowd pressed close, anxious, curious, scandalized. The twelve Christians from Scillium had refused to honor the emperor’s genius—his divine spirit. That refusal was treason.

“Swear by the genius of the Emperor,” commanded Saturninus, his voice like polished steel. “And we will let you go. You may believe what you like, but obey Rome.”

Speratus stepped forward before the others could speak. His beard was streaked with gray, but his voice did not waver. “I do not recognize the authority of this world over my soul. I have no emperor but Christ.”

A murmur swept the forum. Even some among the officials shifted uneasily. This was not just civil disobedience—it was divine defiance.

“We are Christians,” added Nartzalus, his lips trembling as he looked skyward, “and we honor no power above Him who sits on the right hand of the Father.” He had heard those words first from a bishop who read Acts aloud in a hidden courtyard—Acts 7:55: “But he, full of the Holy Spirit, looked up to heaven and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God.” The martyr Stephen had seen it, just before stones ended his earthbound sight. Today, perhaps, they too would see.

“You refuse the wealth of our laws, the safety of the Pax Romana, the wisdom of our courts?” Saturninus asked. “What scrolls give you greater knowledge than ours?”

As if in answer, a woman named Cittinus unwrapped a stained leather pouch. Inside it, a fragment of parchment trembled in the breeze—the Greek words faded from time and breath. It was the Psalms, she said, handed to her by her mother on the day she clouded her first baptism pool with tears of faith. The proconsul snorted and dismissed it as superstition.

Then the sentence was read: execution by the sword.

Twelve Christian souls—anonymous in imperial records save for their names, preserved only by scribes and memory—were marched to the fields outside the Roman walls. No gruesome lions, no burning stakes. Only swift steel. Rome knew the dangers of spectacle: silent courage on the scaffold could stir hearts louder than mobs in the amphitheater.

As the twelve knelt beside each other, none pleaded, none begged. Speratus whispered a final psalm as the executioner raised his blade. "You guide me with your counsel, and afterward you will receive me to glory."

And then silence fell over the North African plain.

What began that day in 180 AD was not silence, though. The record of their trial—the Acts of the Scillitan Martyrs—escaped the imperial purge. Copied by monks in hidden scriptoria, passed hand to hand across sea and sand, their confession made it as far as Hippo, where a boy named Augustine would one day read of their bold stand. He would walk among their tombs, preach over their memory, and urge his people that the bishop’s crozier and the martyr’s blood served the same King.

In Carthage, where their blood darkened the dust, believers built a small shrine—a simple oratory first, then a domed chapel, its floor inlaid with the Chi-Rho above olive branches. By the time Tertullian defended the faith against Rome’s accusations, he called their witness “the seed of the Church in Africa.”

Some doubted the names—perhaps distorted in time—or whether all twelve truly came from Scillium. Others whispered that one was spared that day, sent to carry the tale. The Roman records remark on their calm, their peculiar joy in dying. One official scribbled, *“They spoke of ‘light and glory better than the sun’s.’ Delirium?”

Yet centuries later, pilgrims journeyed from Tunisia and Numidia to lay flowers and prayer at their tombs. A basilica rose over their bones, its mosaic ceiling depicting heaven opened, like in Stephen’s vision—Christ not seated, but standing, as if to receive them.

Africa’s Church—so often overshadowed—had been claimed not first by missionaries with parchment, but by those who bled for it. Before Alexandria surged with Coptic scholars, before Cyprian and Augustine shook councils with their pens, twelve farmers and wives, readers of Psalms and Acts in outlawed assemblies, had held fast.

And it was enough to plant a continent’s faith.

On July 17, the Church still remembers, not only their names, but their chosen silence—a silence louder than any blade or law. They did not defy Rome to destroy it, but because they worshipped a throne higher than Caesar’s.

And from the sands of Carthage, watered in blood and psalm, rose cathedrals, conversions, and a cry that still echoes: Jesus is Lord.