In the chill of a May morning in 1671, the iron clank of Bedford Gaol’s gate echoed like a funeral bell. A man in patched wool was led inside, the coarse tread of soldiers behind him. He was neither thief nor traitor, but John Bunyan, a tinker by trade and preacher by calling, arrested under the Conventicle Act for proclaiming Christ without license from the Church of England.

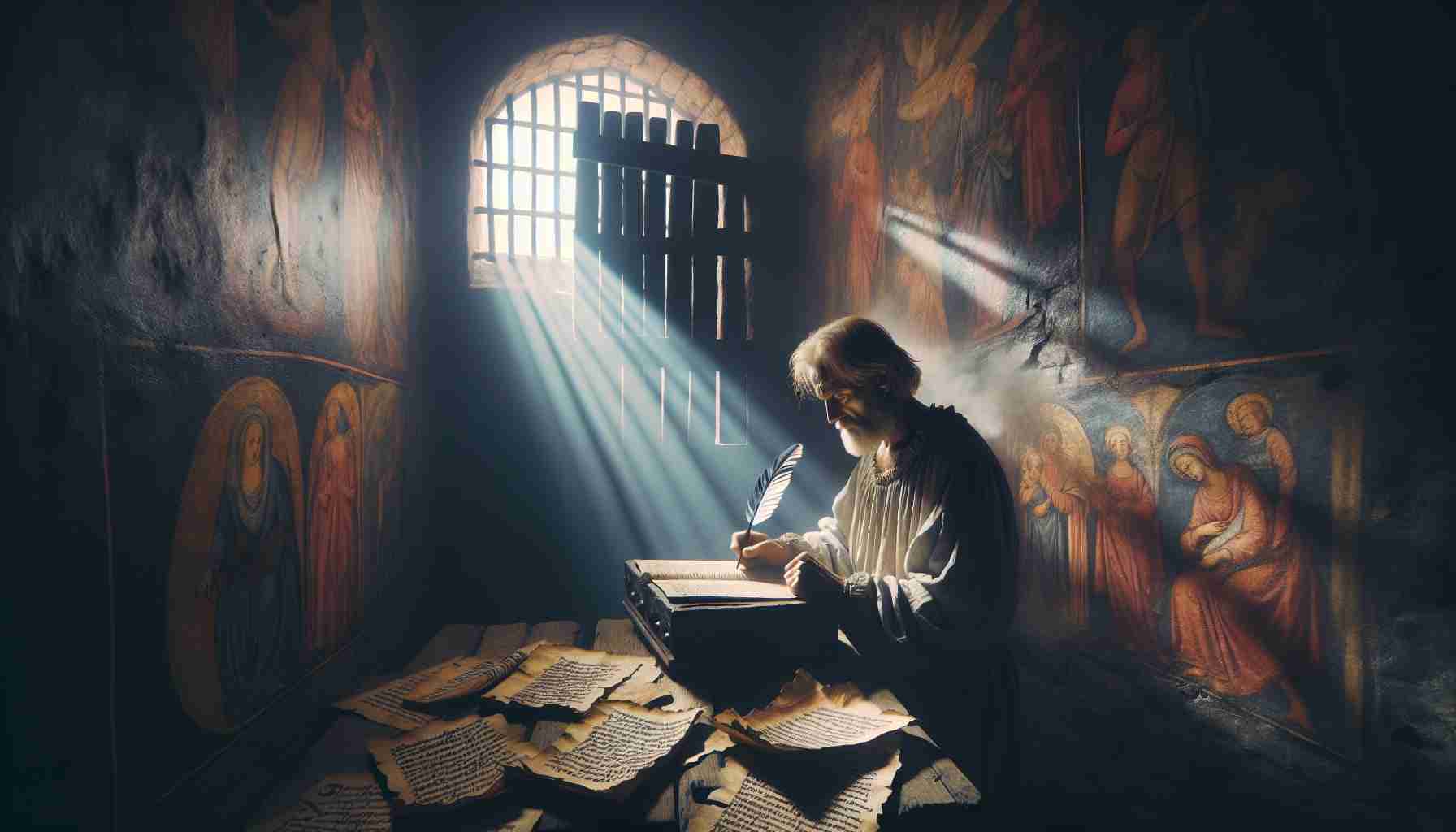

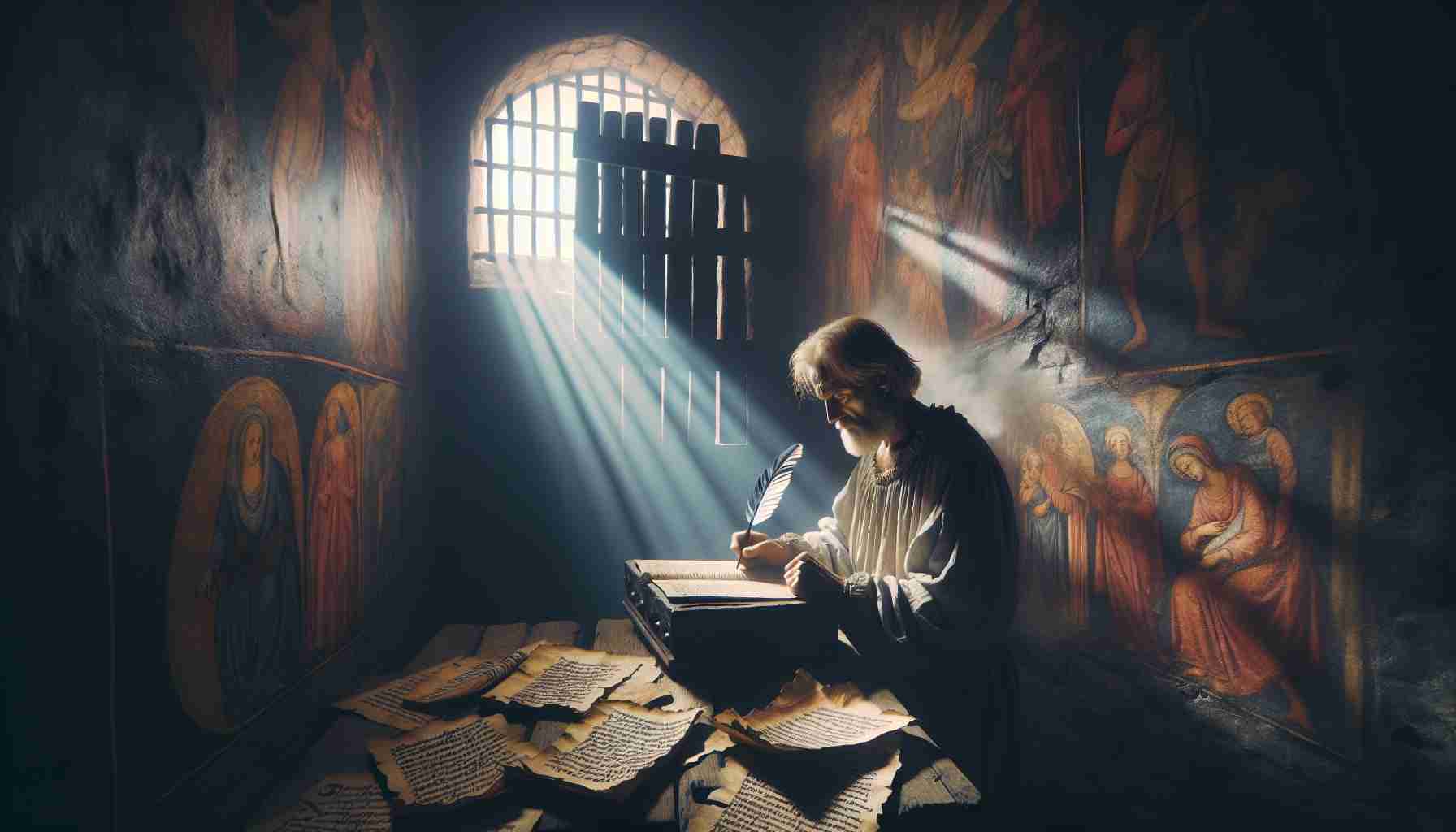

His cell was stone and straw, only a slit window for light, but he carried with him a worn Geneva Bible and the name of Christ pressed firmly on his soul. His crime: speaking truth in barns, fields, and forests, wherever hearts gathered hungry for the Word. Though he stood poor before the magistrates, he had not begged for freedom. When offered release in exchange for silence, he had said, “If I was out of prison today, I would preach the gospel again tomorrow.”

Days melted into months. His youngest daughter, blind Mary, would sometimes visit, her soft hands tremulously threading through the bars, her voice like water upon thirsty soil. He ached for his wife and children, but the call of faith burned hotter than any hearth-fire.

Within that stony cell, time grew long. Yet a fire of vision stirred—a dream stranger than sleep. The walls became as mountains, the straw as winding paths. And so ink met parchment, and Bunyan wrote.

He imagined a man named Christian, bearing a heavy burden, fleeing from the City of Destruction. Led by Evangelist and guided by Scripture, Christian traveled through the Slough of Despond, encountered Doubting Castle, and weathered Vanity Fair. Each step mirrored the spiritual struggle of every believer wrestling toward the Celestial City. Characters walked from Scripture’s marrow—Faithful, Hopeful, Apollyon—and places took root in memory, as tangible as Jerusalem.

The manuscript grew slowly. Quills broke. Ink ran dry. Rats worried the bindings. Yet he wrote on, each word forged in the furnace of trial. 2 Corinthians 4:17 whispered over every page: "For our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all."

Outside, England shifted. King Charles, beneath velvet and crown, danced between toleration and persecution. Inside the prison, Bunyan's story deepened. Not just a tale—it was theology cloaked in narrative, the journey of the soul in allegory’s form. His burdened Christian was every pilgrim.

When freedom came in 1672 through the Declaration of Indulgence, Bunyan stepped into daylight a different man. His hands were ink-stained, his hair grayer. But in his satchel lay a manuscript, hand-bound and trembling with truth.

The Pilgrim’s Progress was printed six years later, in 1678. Word spread like fire. From inns to pulpits, in Puritan homes and quiet chapels, the tale turned pages in eager hands. No book save the Bible would be read more, translated into over two hundred languages, crossing oceans, emboldening missionaries, guiding slaves, awakening saints.

Some scholars later puzzled how a man with meager education wove such enduring language. How a prisoner, denied pen and freedom in harsh England, had crafted a masterpiece. But those who knew the cost said suffering had been his teacher.

Bunyan did not seek greatness. He sought God. In stone silence he had heard the Holy whisper. His chains had not shamed him but shaped him, just as Paul had written from his own prison: “Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are renewed day by day.”

Once, Bedford’s market square had known his voice. Now, centuries later, generations know his footsteps, tracing Christian’s path from despair to glory.

The jail itself still stands in Bedford, walls re-set in later buildings, but that cell—primitive and narrow—is remembered. Pilgrims come to trace the legacy, as if the air still holds echoes of quill against parchment, of prayers whispered under moonlight.

And in that trembling space where stone met spirit, John Bunyan's heart had declared what lecture halls and bishoprics could never teach: that eternal fruit is often born in bitter fields. That suffering—which the world calls waste—is the womb of wonder when offered to the hand of God.

From such darkness came light. From prison, a path.