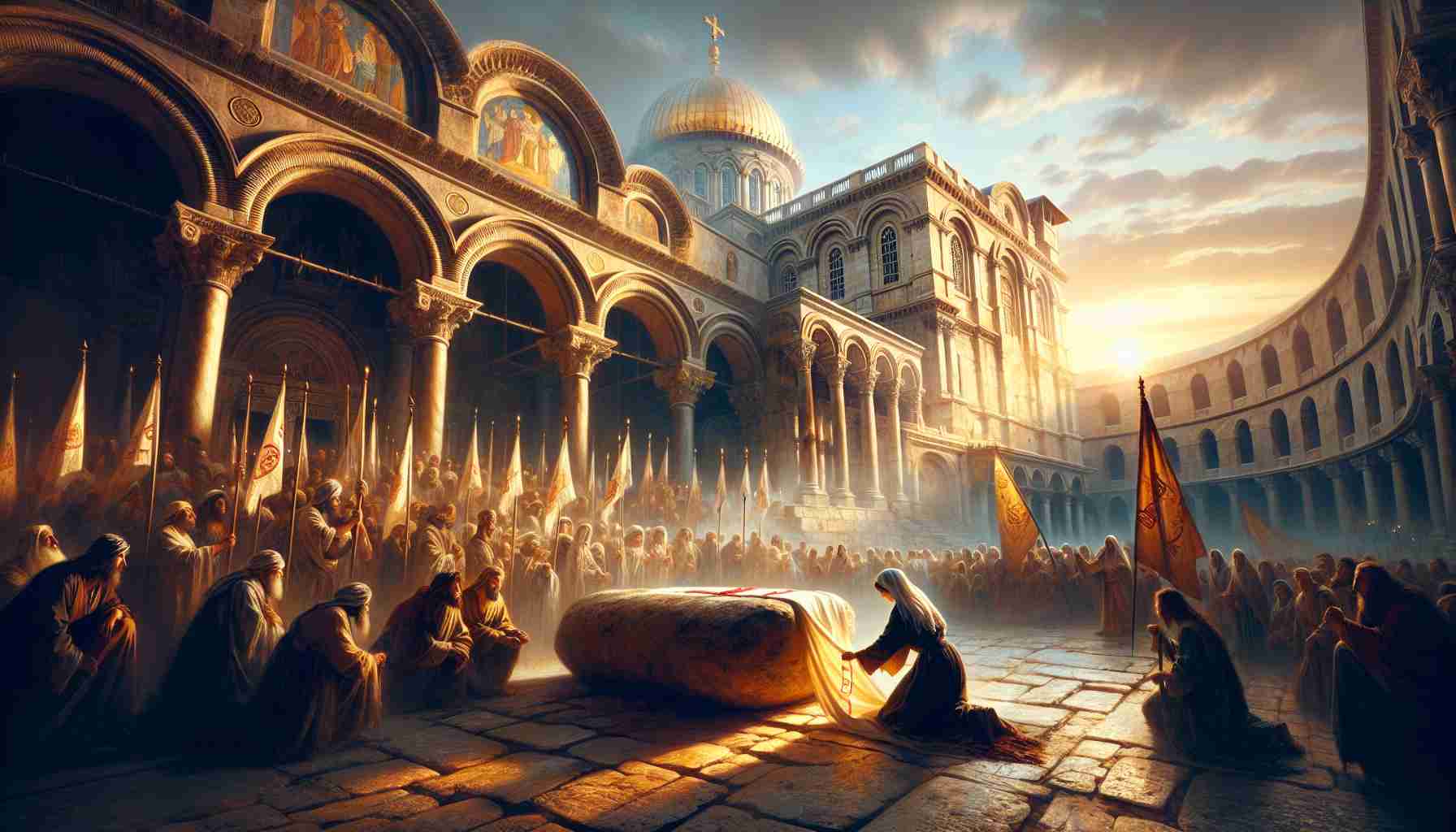

The sun pierced the morning haze over Jerusalem like a polished lance. Bells rang across cobbled alleys, their jubilation sweeping upward to the ancient hills. Men and women gathered near the gates of the basilica—some local, many from distant provinces of the empire—cloaked in the dust of pilgrimage. The year was A.D. 351, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was to be rededicated.

The Roman banners, once emblems of conquest, now bore the Chi-Rho: Christ’s monogram flying where eagles once declared Caesar’s dominion. The basilica—rebuilt under the decree of Emperor Constantius, the son of Constantine the Great—waited like a resurrected giant. Yet it was his grandmother, Helena, who had journeyed to this land decades before, with prayers in her heart and visions of the cross in her sleep.

Stone by stone, the pagan shrines had been torn down. At the site where Roman soldiers had once mocked Christ with thorns and vinegar, Helena ordered excavations. A legend began there—that three crosses were discovered, and the one that bore the Savior was revealed when a sick woman touched it and was healed. That relic was sealed in the heart of the new basilica, beneath the soaring dome, behind veils of incense and myrrh.

Now, before the faithful, the massive doors groaned open, and torchlight glinted off polished marble columns and golden icons. Priests in shimmering vestments chanted in Greek and Latin. Smells mingled—the sharp resin of frankincense with the lingering soot of freshly-lit oil lamps. The air seemed heavier within, sanctified by reverence and memory.

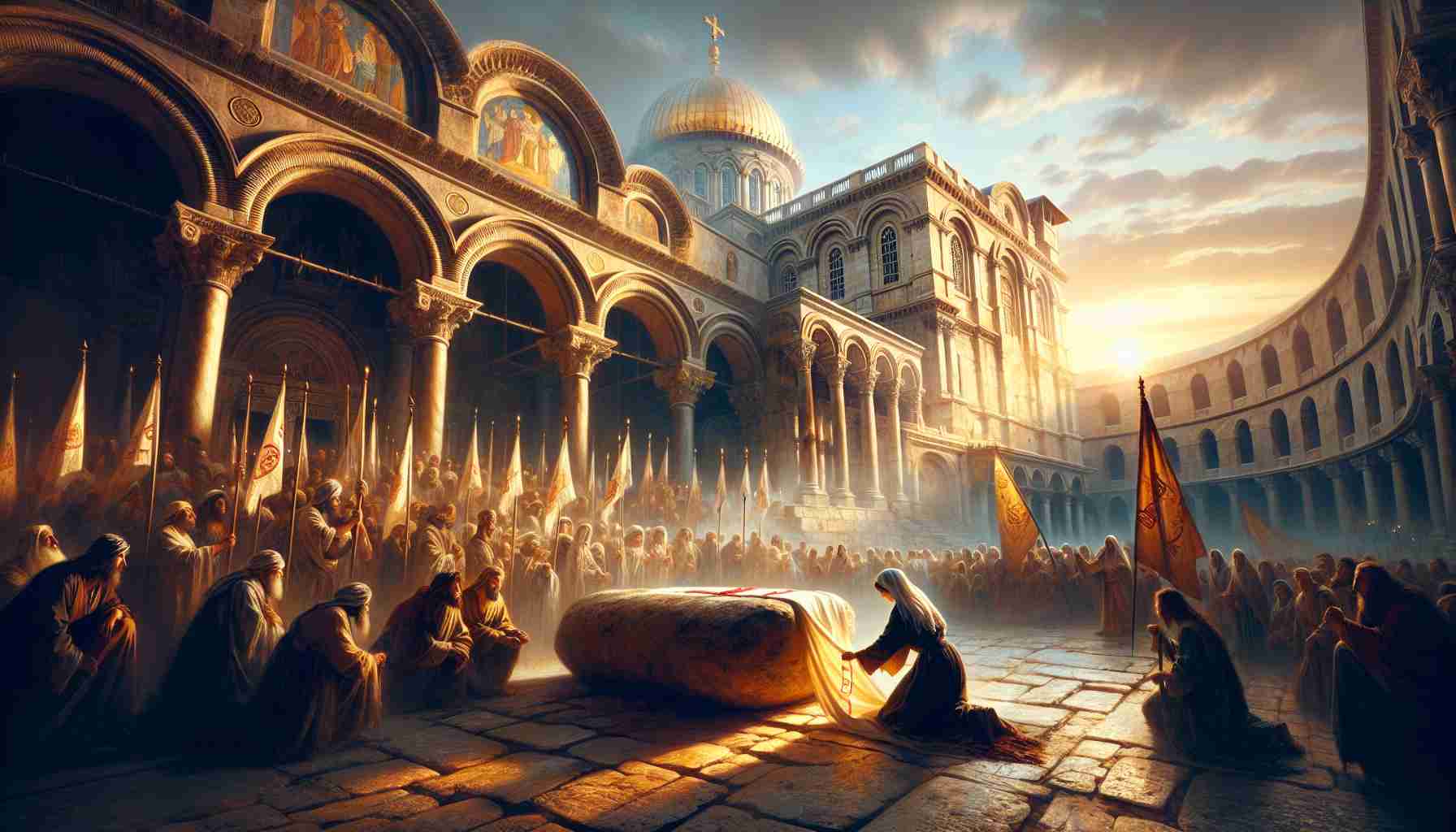

At the church’s central axis rose the rotunda, the Anastasis—the Shrine of the Resurrection. Encased within it, hidden beneath layers of precious stone and wood, was the tomb believed to be Christ’s, the one that was hewn from rock yet found empty at dawn. John 19:17 told of His burdened walk to Golgotha, bearing the cross. Now, on that very hill, sanctified beneath centuries of Roman strata, pilgrims traced their fingers along the sacred stone, where burial gave way to glory.

A woman pressed close to the sepulchre, holding a strip of linen embroidered with faded crimson thread. Her son, lost in battle in the northern reaches of Gaul, had died calling the name of Christ. She whispered fervently—pleading not for his return, but for confirmation. That the tomb was truly empty. That her son had not prayed into silence.

No voice answered, but the silence of that chamber was charged—as if the very air remembered a body once resting there, and the divine breath that stirred it to life.

Outside, bishops raised their arms. The blessing swelled—spoken over Jerusalem, over every rock and roof and planted millet field. The church had been desecrated not long before, when the Persians swept through in fire and fury. Its dome had blackened, its altars pillaged. But rebuilt it stood again, not just as stone, but as defiance—against Rome's pagan past, against time, against death itself.

Rumors flourished even amid reverence. Some whispered that the true tomb lay elsewhere, buried beneath Mount Zion or far beneath the foundations of the Temple Mount. Others argued that the cross Helena had found was a pious fabrication, born of imperial enthusiasm and the politics of piety. Yet faith paid no toll to archaeology. For each stone laid was a testament to the God who died like a criminal and rose like a king.

Pilgrims carried water from the Jordan in clay jars, scraps of dust from Gethsemane hidden in satchels, and now—in silent awe—they reached toward the tomb’s rough walls as if to anchor themselves to something eternal. The journey marked them. Feet blistered on holy ground, eyes burned red from tears and desert wind, but hearts returned changed.

From Antioch to Alexandria, stories spread. Of a mighty church that stood where earth briefly held heaven. Of a hollow tomb, and of a light no emperor, no legion, could extinguish.

The bells pealed again—slow and sonorous, echoing a promise cast down the centuries.

In that hallowed place, Jerusalem no longer belonged solely to emperors or armies. It belonged to the broken who believed. To those who still sought Jesus—not among the dead, but among the living. Not in Caesar’s marble halls, but at the foot of a rugged cross and before a quiet, empty tomb.