The bells of Westminster tolled a mournful hour as the summer sunlight gilded the stone walls like blood on steel. July 28, 1540—the day a reformer’s ally fell, not by sword in battle, but beneath the axe of the king he had served too well.

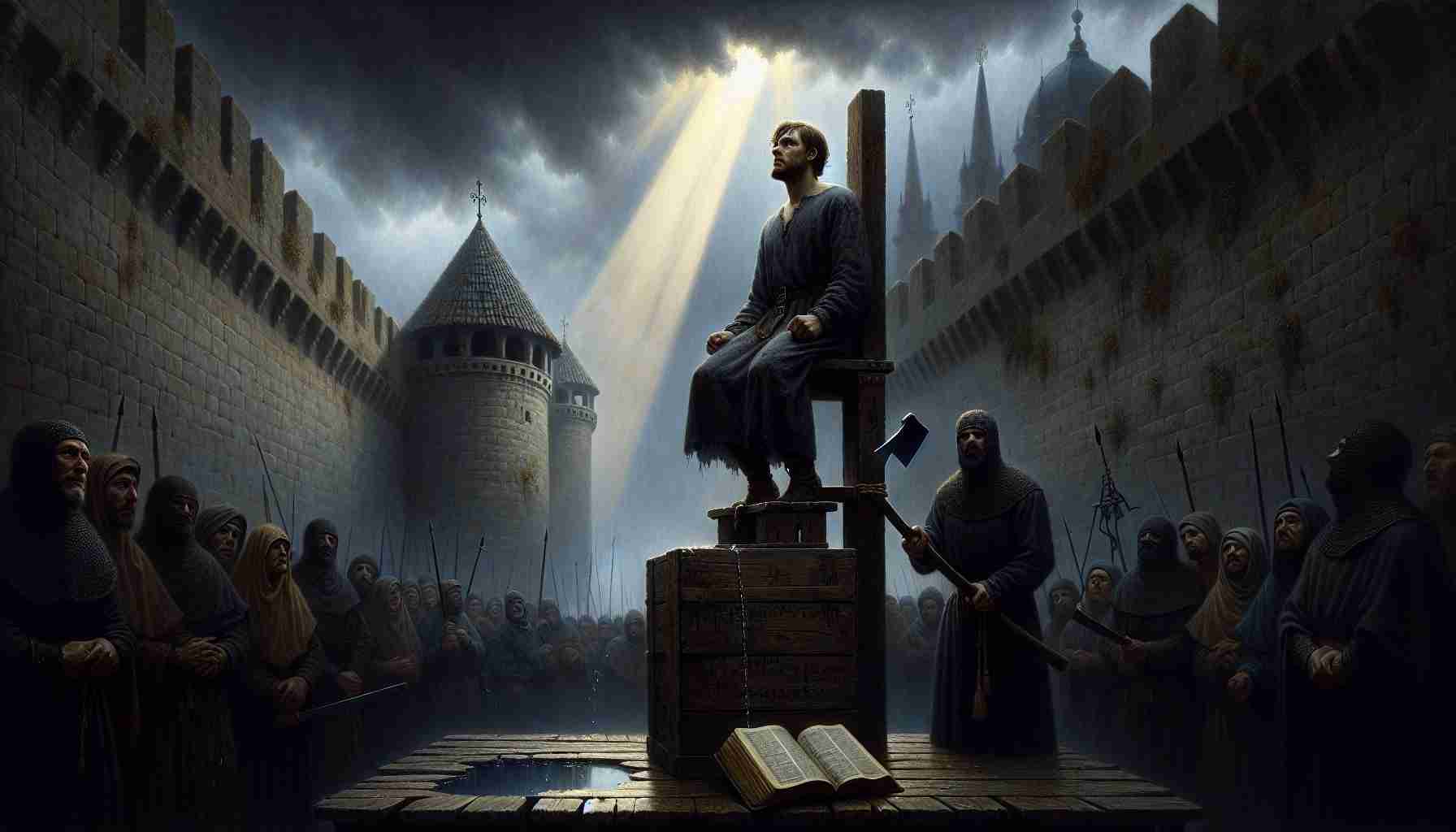

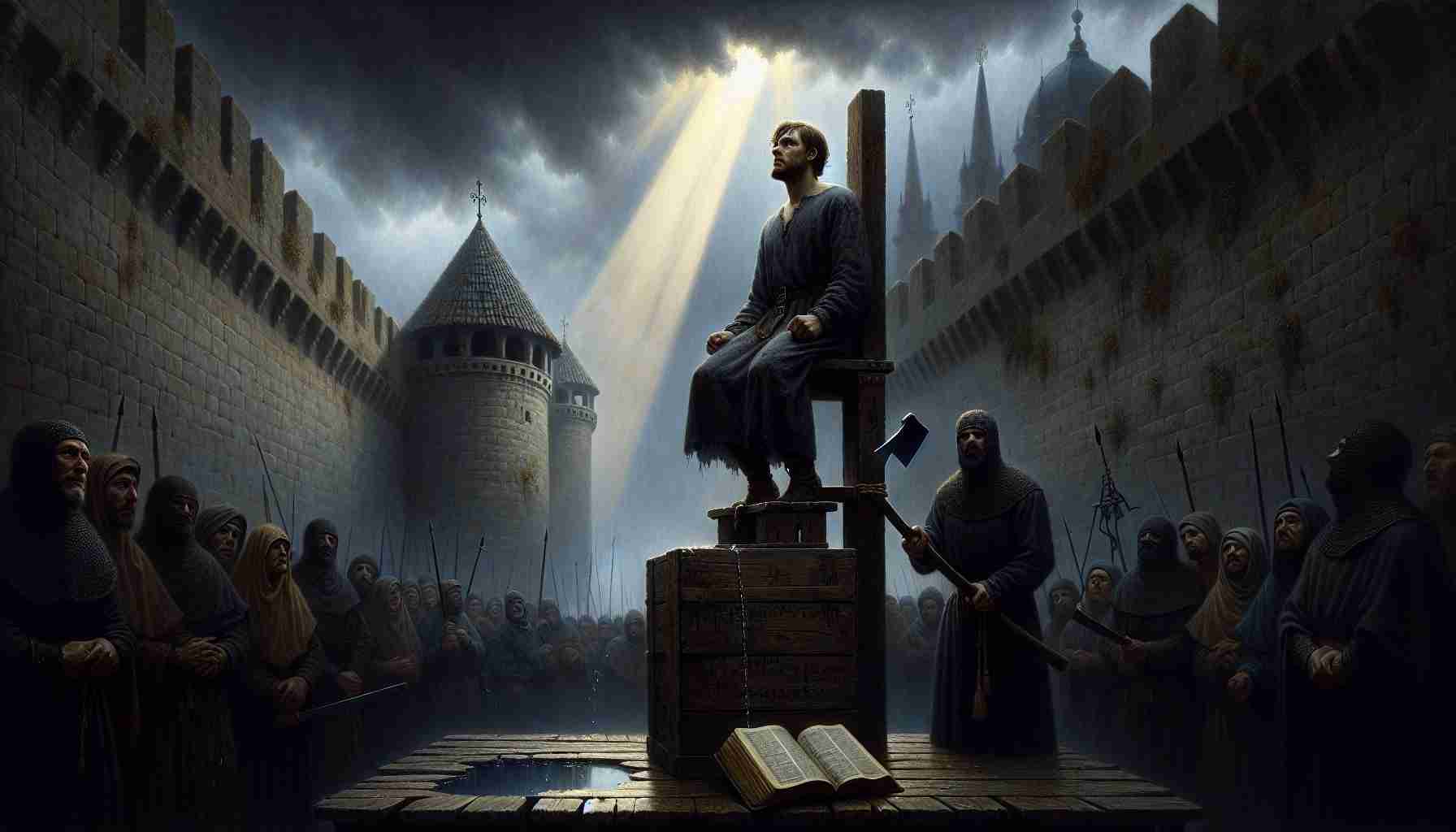

Thomas Cromwell ascended the scaffold quietly, draped in the coarse black of condemned nobility. A murmur rippled through the crowd, not the jeers one might grant to a fallen traitor, but the hushed confusion of those uncertain whether justice or fear had won the day.

He looked not at the gathered nobles nor the bishop watching from beneath white-and-purple robes. His eyes turned instead toward the heavens, the Psalm often read at times like these echoing in his chest: “Put not your trust in princes, nor in the son of man, in whom there is no help.” The words of Psalm 146:3 came to him not as condemnation, but vindication.

Only a few years before, Cromwell had been the architect of a new England, stripping monasteries of their wealth to restore it to the Crown, scattering relics and chalices in the name of purity and reform. He had championed the English Bible, so that even the plowboy at work in the field might know the Word of God more clearly than a monk shrouded in Latin hymns.

But Henry VIII was not God.

The king’s favor had once burned fiercely for Cromwell, lifting him from blacksmith’s son to Earl of Essex. Yet one misstep—a foreign marriage alliance with Anne of Cleves, more political than romantic—crumbled the brittle trust between them. Whispers in the court became daggers. His enemies, old allies of the old Church, circled like carrion. Norfolk. Gardiner. The Duke’s velvet sleeves hid hands eager to hold the levers of power that Cromwell had so long controlled.

On the scaffold, sweat beading upon his temple, Cromwell offered no long confession. He bore no false witness. He had corresponded with Lutherans, yes—what reformer had not sat with fire too closely? He had made enemies. He had used the king’s anger as an arrowhead to pierce the hearts of abbots and friars. But in it all, he believed he served both the throne—and the Lord.

The executioner, trembling from either fear or shame, lifted his axe high, ill-practiced in his work. It would take more than one blow to sever the reformer’s neck. The crowd turned their faces. Some wept. Others, in silence, remembered the Bibles in their homes, the churches no longer cloaked in incense and Latin chants.

In Canterbury Cathedral, where the seat of English Christianity had once bowed to Rome, the echoes of reformation still trembled along the high arches. Cromwell's reach had marked even there, toppling saints from niches, dissolving the shrine of Thomas Becket—the martyr of church over crown. Cromwell had reversed history with royal blessing. Now, history reversed him.

Yet what man can grasp Providence? Even in the wake of Cromwell’s fall, the English Bible would remain. The flames lit to burn reformers like Tyndale and Latimer would not consume the truth they bore. Henry's wrath had struck a servant, but the seed of Reformation had already taken root in the people.

Later, in the Tower's shadow, a lone scribe penned a line into the margins of his English Psalter: “A just man may fall at dawn, but the Lord shall raise his cause at dusk.” It was not Scripture, yet it echoed its spirit.

In Lambeth, a widow whom Cromwell had secretly aided—restoring her land taken by corrupt monks—read aloud from a worn copy of the English New Testament he had helped bring to print. Her child listened wide-eyed as she spoke in the tongue of their own hearth, no priest needed to interpret God's love.

A fallen minister. A severed head. A scattered court.

But the Word remained.

In years to come, as monarchs shifted like weather vanes toward Rome and away again, the stones Cromwell laid would not be unbuilt. Reform would rise and fall, yet persist. His hands may not have been clean, but his labor yielded fruit no axe could destroy.

And so the story of Thomas Cromwell, complicated servant of the Reformation, ends not with betrayal, but with a truth far older than any English crown: “The Lord shall reign forever, thy God, O Zion, unto all generations.” Psalm 146:10.

Even in the shadow of the gallows, righteousness found its voice.