Wind moaned through the hollow arches of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, as if the stone itself remembered sorrow. It had stood for centuries, lodged like a sacred thorn in Jerusalem’s flint-gray heart—a monument built atop battle-scorched ground, raised where pilgrims believed Christ had died, been buried, and risen anew. Beneath its domed ceiling, light filtered through incense-smudged windows, casting flickering shadows upon conscious faith and bitter memory.

The year was 638. As the muezzins’ chants rose beyond the city walls, Khalid ibn al-Walid’s army prepared to enter Jerusalem. The golden dome upon the Temple Mount shimmered under a red dawn. The cross that once glimmered above the skyline now leaned into shadow.

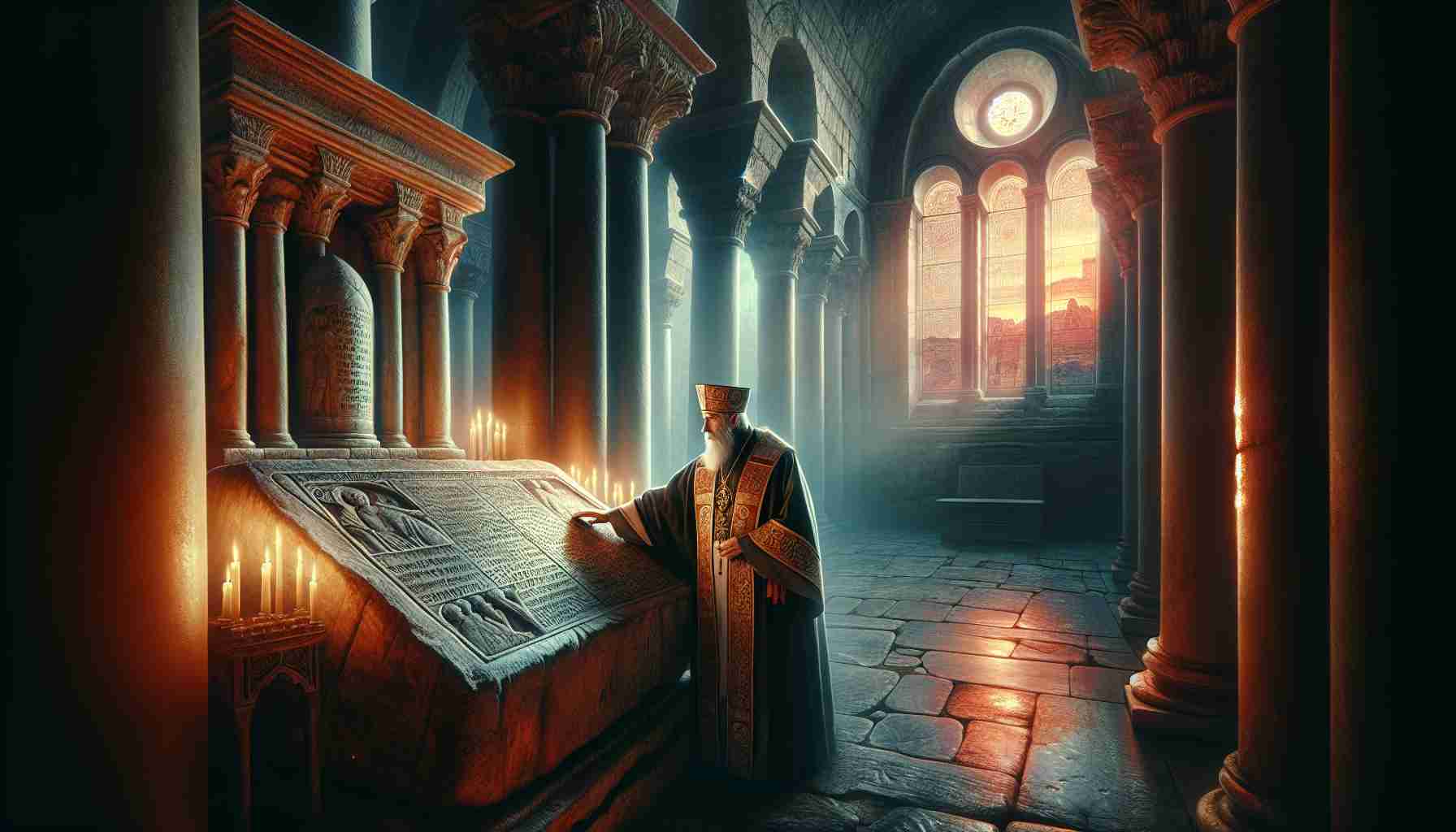

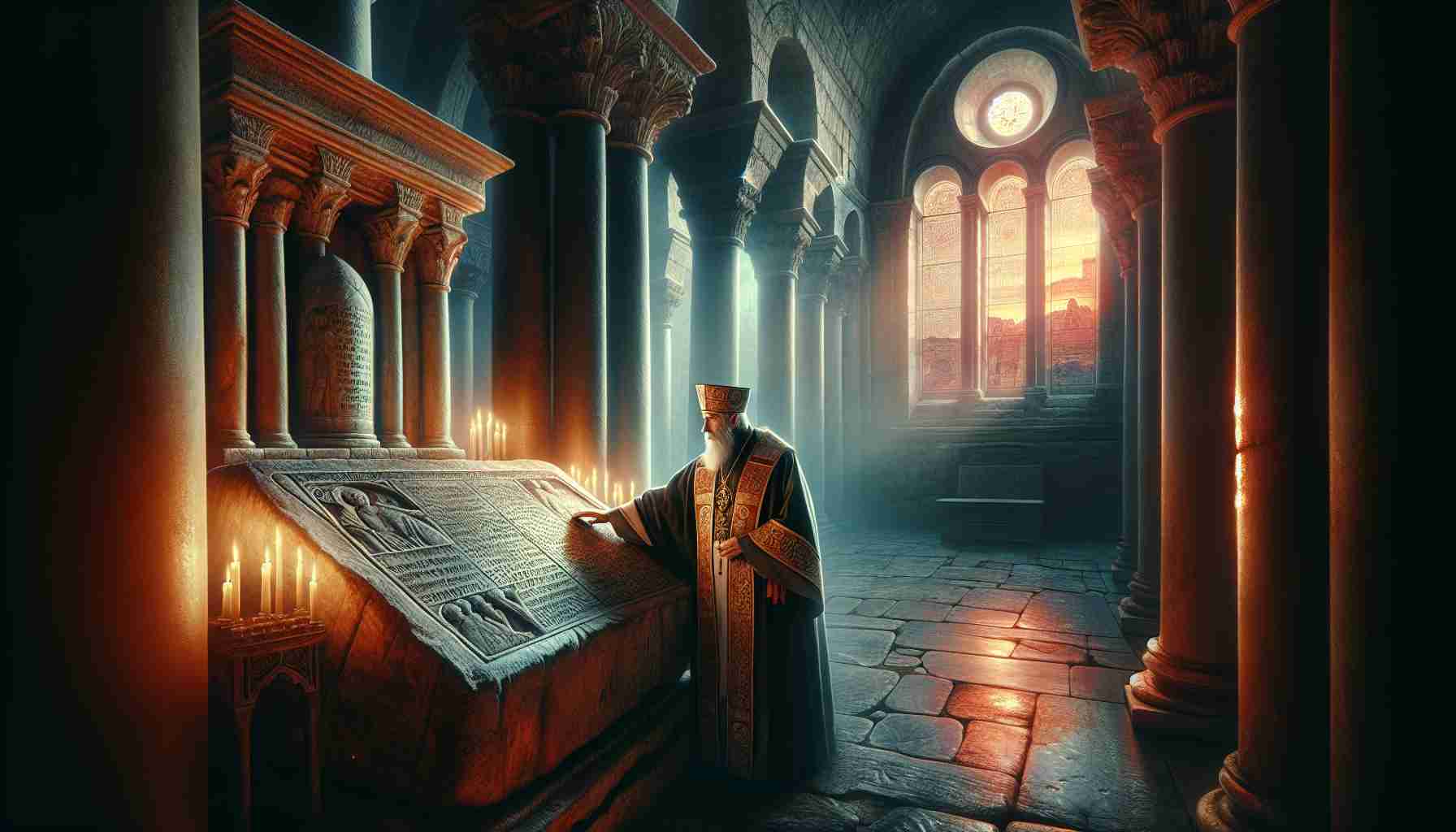

Soft sandal steps echoed within the church courtyard. Bishop Sophronius, aged and bent like an olive branch in winter, stood beside the Stone of Anointing. His fingers, gnarled by time and writing, traced the etchings of old Greek prayers worn into the marble. He had memorized Paul's words since childhood: “And if Christ be not risen, then is our preaching vain, and your faith is also vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14).

Now, after Muhammad’s death in the deserts of Arabia six years past, his followers surged like waves across broken empires. Persia had wept already. Damascus lay under crescent shadow. And now they came—peaceful in word yet unyielding in terms.

Sophronius knew the holy city could not withstand another siege. The walls still bore scars from Heraclius’ wars against Persia. But it was not swords he feared. It was the silence—of altars forgotten and Christ’s tomb passed by.

He turned when Abba Theodulus approached, eyes rimmed with sleepless red.

“They will not stop at the gates,” the younger man murmured.

“They should not,” the bishop replied, calm as carved granite. “If they take the city, they must see what it holds. Not gold. Not battlements. But the place where love died and rose again.”

Before the noon sun struck its zenith, the Caliph’s emissary entered through Jerusalem’s eastern gate. His name was Umar. No golden armor adorned his frame. He wore simple wool, and his eyes bore that same intensity Sophronius had seen in Christian martyrs—fire with purpose larger than empire.

The bishop took him first to Golgotha. No altar fires burned today, yet the air filled with the gravity of blood once spilled. Umar said little, but his eyes moved across the stone where the cross had once stood—a rough square beneath the Rotunda’s dome, held sacred by centuries of tears.

They climbed downward then, to a cavity hewn in limestone bedrock—the tomb. Sophronius paused before the entrance. Legend said Helena, Constantine’s mother, had unearthed it in the fourth century, guided by prayers and local rumor. She had split temples and sacrifice altars to uncover what the Empire could not forget: a chamber where death itself had been reversed.

“We protect this ground not for power,” Sophronius said softly, “but because here eternity touched earth.”

Umar nodded. “And your people believe He rose?”

“It is not just belief,” the bishop said. “It is why we breathe.”

No sword was drawn. No torch was raised. Umar listened, then made terms. Christians could pray. Their churches would stand. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre would be guarded. No Muslim prayer would be offered inside. This ground, at least, would not be taken by force.

Still, the city wept. Some feared that Christ had forsaken them. That Muhammad’s death had unlocked a fury Christians could not match. But others—priests, old soldiers, widows—clung tighter to the cross, not looser.

Beyond the city walls, apologetics flourished. Scholars like John of Damascus rose in later decades, born in that same conquered land, writing from monasteries near the Jordan River. They studied both Christ and the Qur’an and defended resurrection as history, not myth. The sharper the rival creed, the brighter their flame burned.

Back inside the church, candles were relit. At night, hymns still floated through the great dome’s arch: “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death…”

Centuries would pass. Crusaders would take the city with bloodied steel. Saladin would retake it with grace. Earthquakes and fires would rage. Yet the church would endure. Even in 1009, when the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim tried to raze it to memory, stones from the original Constantinian structure were salvaged and woven into new altars.

Today, stone worn smooth by millions of hands still testifies—not just to Jesus’ grave, but to the fierce endurance of faith when challenged by change. Muhammad’s death did not bring Islam’s end—it was its beginning. But in that same breath of history, Christ’s followers found new courage, not compromise.

For when faith stands in a rival’s shadow, resurrection becomes not just doctrine, but defiance. Not only memory, but mission.

And so the tomb stood empty, as it had since the morning the women found the stone rolled aside. Nothing else mattered more.