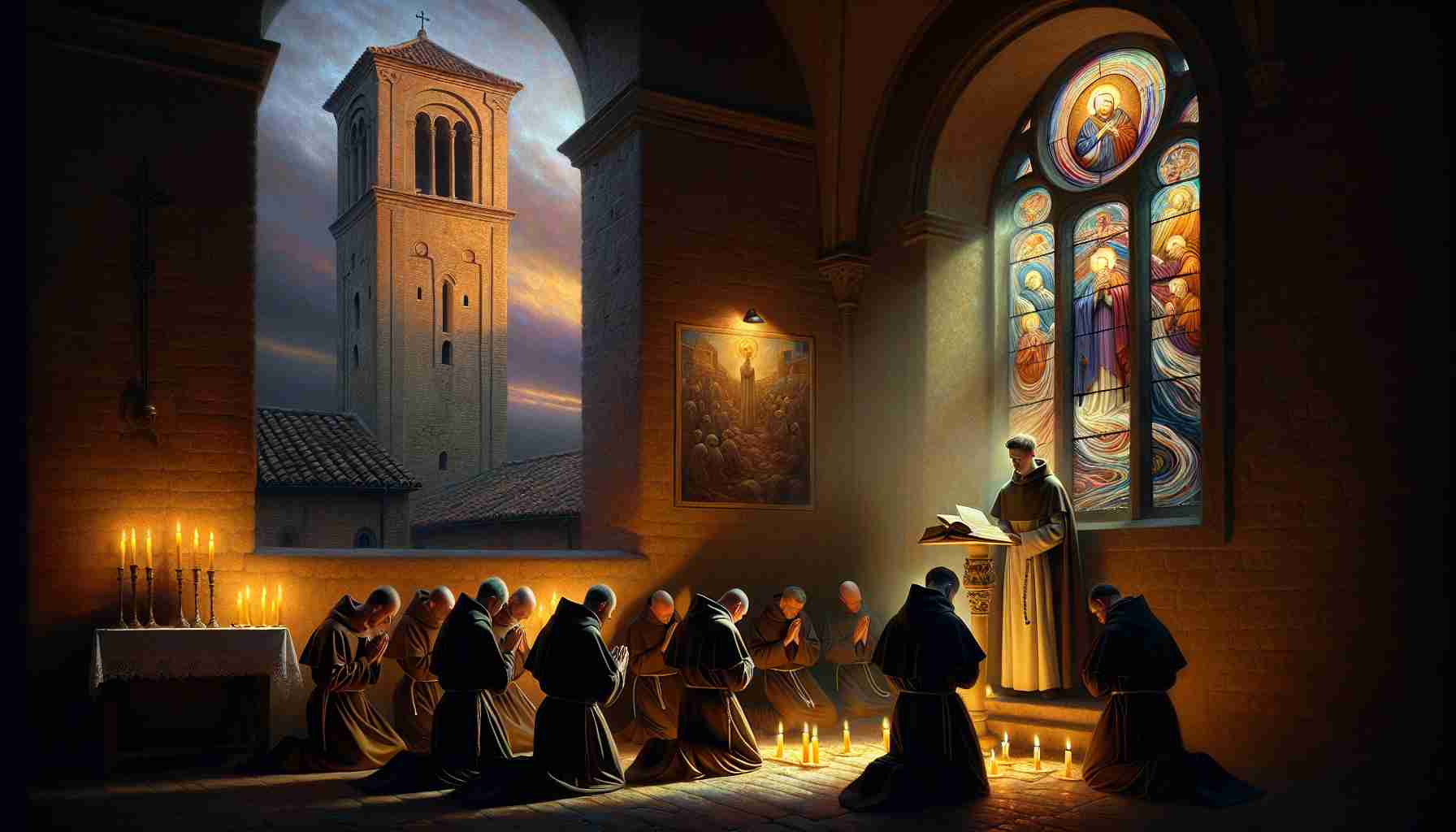

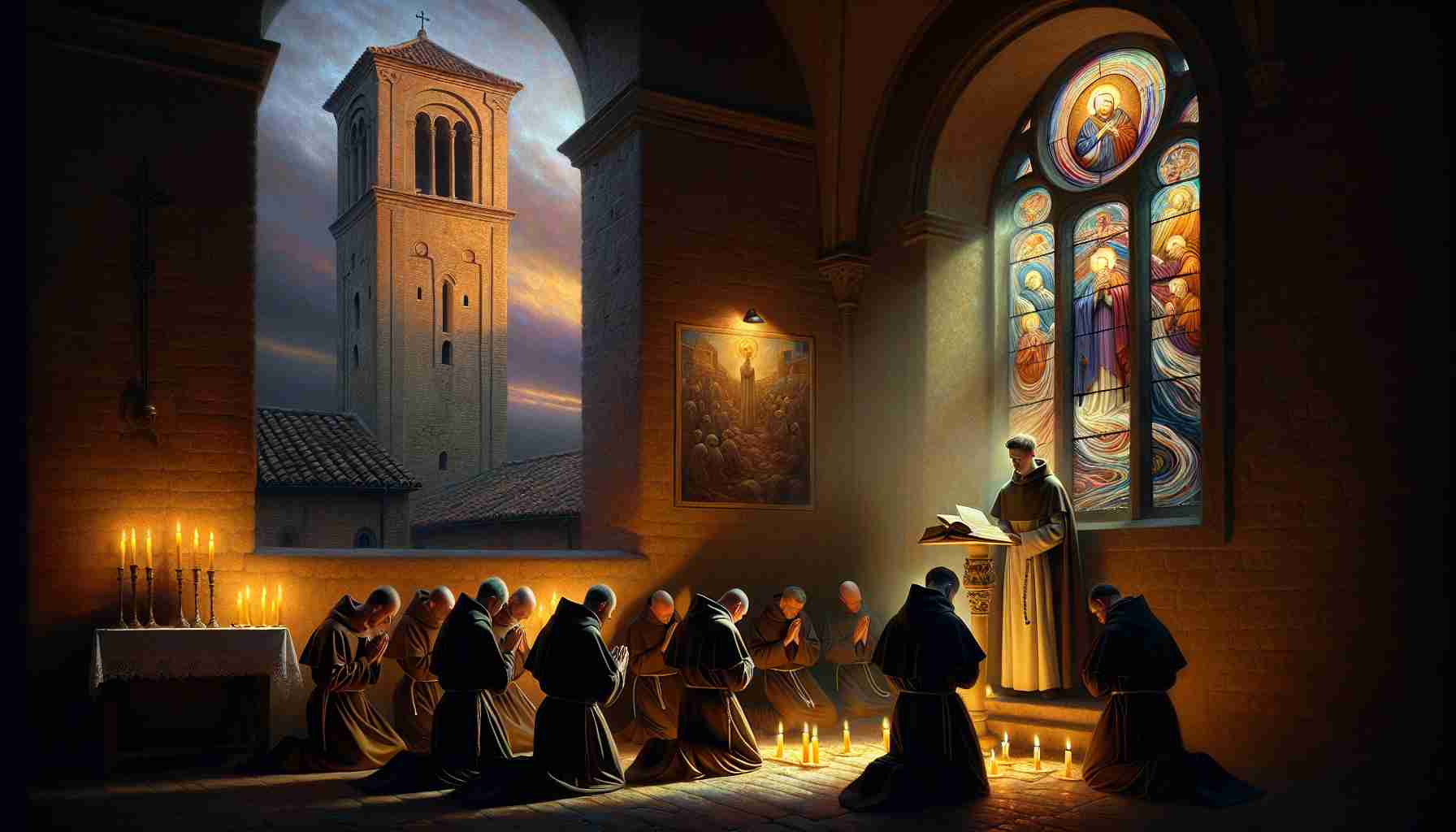

The bells of Padua tolled mournfully on that June afternoon in 1231, their echo folding across the terracotta roofs as if the sky itself were grieving. Inside the arcaded walls of the Arcella monastery, candles guttered in vigil. Brother Anthony lay still beneath a thin woolen blanket, the frailty of his thirty-six years etched deep into his serene features. Around him gathered friars in silent prayer, some weeping quietly, for they knew the voice that had thundered the truth of Christ in plazas and cathedrals would speak no more.

He had not always been called Anthony. Born Fernando in Lisbon, he'd first served as an Augustinian canon. But it was the sight of five martyred Franciscans—beheaded in Morocco, their bodies returned through Seville—that set his soul ablaze. He cast off all worldly ambition and donned the humble brown robe of St. Francis, taking the name Anthony and praying, even then, to die a martyr. God, however, had other designs.

From the pulpits of Rimini to the marketplaces of Toulouse, Anthony did not merely preach; he accused, he wept, he invited. Crowds swelled as miracles unfurled—knotted tongues untwisted mid-sermon, the sick rose from their mats, heretics left debates silent and converted. His words moved not only minds but sinew and stone. In Rimini, when scoffers shunned him, he turned to the waves, preaching to fish until they surfaced in thousands, heads above water, as still as monks.

“Go into all the world and proclaim the gospel to the whole creation…” (Mark 16:15). He lived these words not from parchment but in breath and fire. When towns refused his entry, he climbed stumps, stood atop barrels, or — famously — even preached within fields as women hung out laundry. Language failed no one; though Portuguese by birth, he spoke with such clarity that Germans, Italians, and Frenchmen claimed he spoke only their tongue. The hearts he sought were found, and that, he often said, was his task—to find the lost.

In his final days, sickness consumed his body, wasting it to shadow. He asked to be carried back to Padua, to die among his flock. As the ox-cart creaked beneath his feeble form amid the sighing cypress trees, he pointed weakly toward heaven and whispered, “I see my Lord.”

By sundown, Anthony was dead.

But Padua was not ready for silence. Within hours, mourners clogged the streets. Merchants ceased trade, children ceased play. Word spread of miracles by his tomb—lameness cured by touch, barren wombs filled, lost things returned. Yet these were not his truest legacy. Souls torn by guilt found peace in his homilies. Thieves returned stolen goods. Drunkards poured their wine into the gutters beneath church eaves.

A year had not passed when Pope Gregory IX sat in Lateran Palace and proclaimed Anthony a saint—a declaration most swift in Church memory. “He shone like a star in the world,” Gregory wrote, “with the brilliance of his teaching, his miracles, and his life.”

They called him Finder of Lost Things, but in the crooked alleyways of Padua, older women whispered he was finder of lost men. And not just the wayward, but lords and lawyers, fathers estranged from sons, wages squandered in gaming dens—all caught in the net of his words.

Even his tongue, unearthed decades later during a ceremonial transfer of his body to the newly completed Basilica di Sant’Antonio, had resisted decay. The rest was earth and bone, but the tongue—rose-hued and moist—lay perfect in its reliquary. Pope Pius XII would later declare it the “Ark of the Testament,” where truth dwelled undiminished.

Beneath vaulted ceilings and Romanesque arches, pilgrims still walk the Basilica’s nave, trailing fingers across chilled marble and whispering prayers of retrieval—for lost treasures, lost loves, lost faith. In the chamber of relics, the jeweled reliquary catches sunlight, reflecting the tongue that preached to the doubting and convicted alike.

Outside, the city of Padua has changed. Streetcars hum where ox-carts once trudged. Neon signs illuminate alleys Anthony once crossed barefoot. But the bell, the one that mourned his death, still tolls from the campanile when June brings the bloom of jasmine, and its call is not grief, but mission—echoing a voice that once called even fish to listen.

His sermons are lost to time, recorded only in fragments and memory, but their fruit remains. The soul cannot unknow the fire once it has caught flame. For Anthony of Padua did not die with his last breath—he moved from earth to heaven, leaving behind hearts still kindled by a tongue unwilling to rot, and a calling: to preach, to seek, and to trust that God, even now, finds the lost.