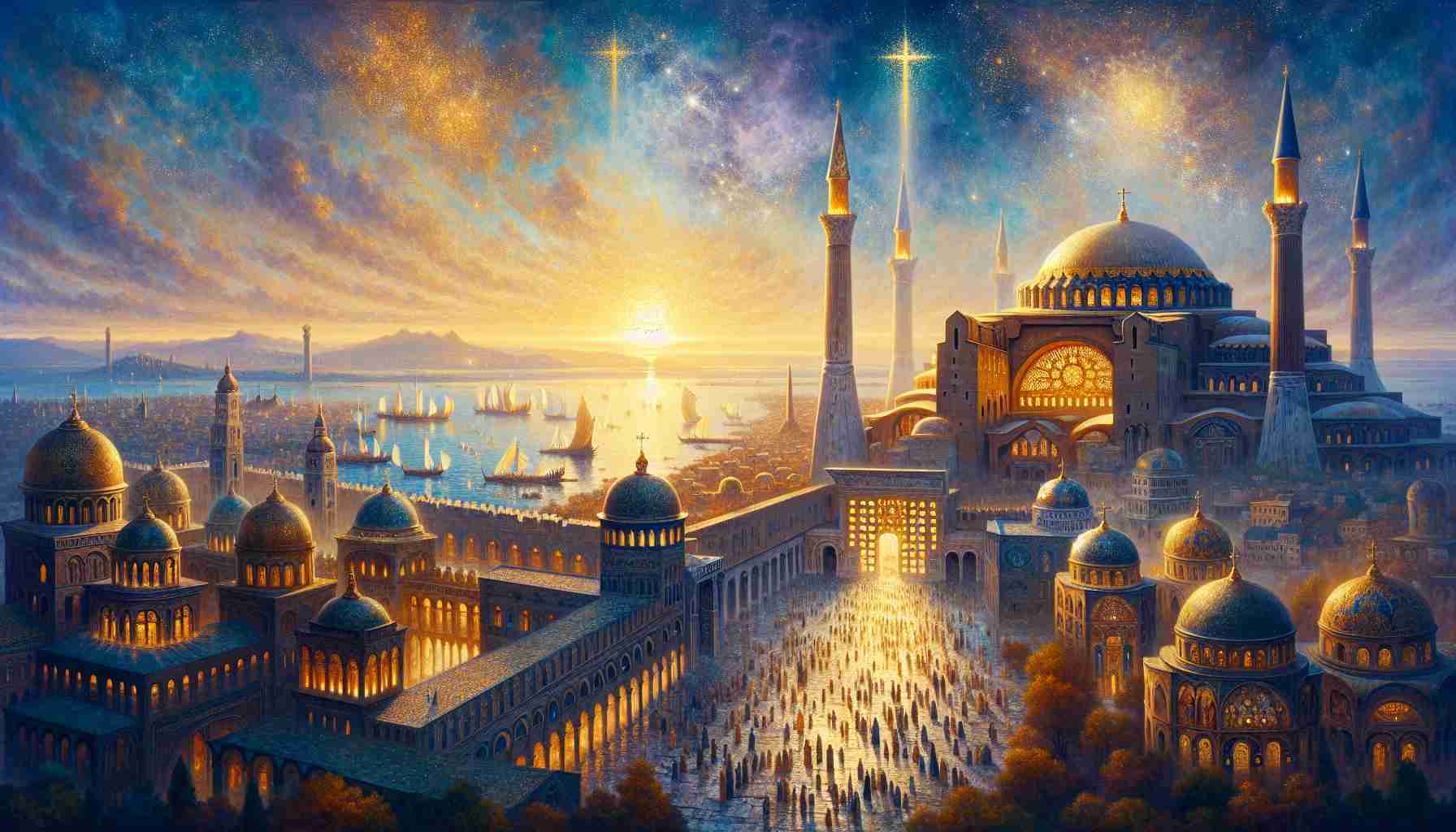

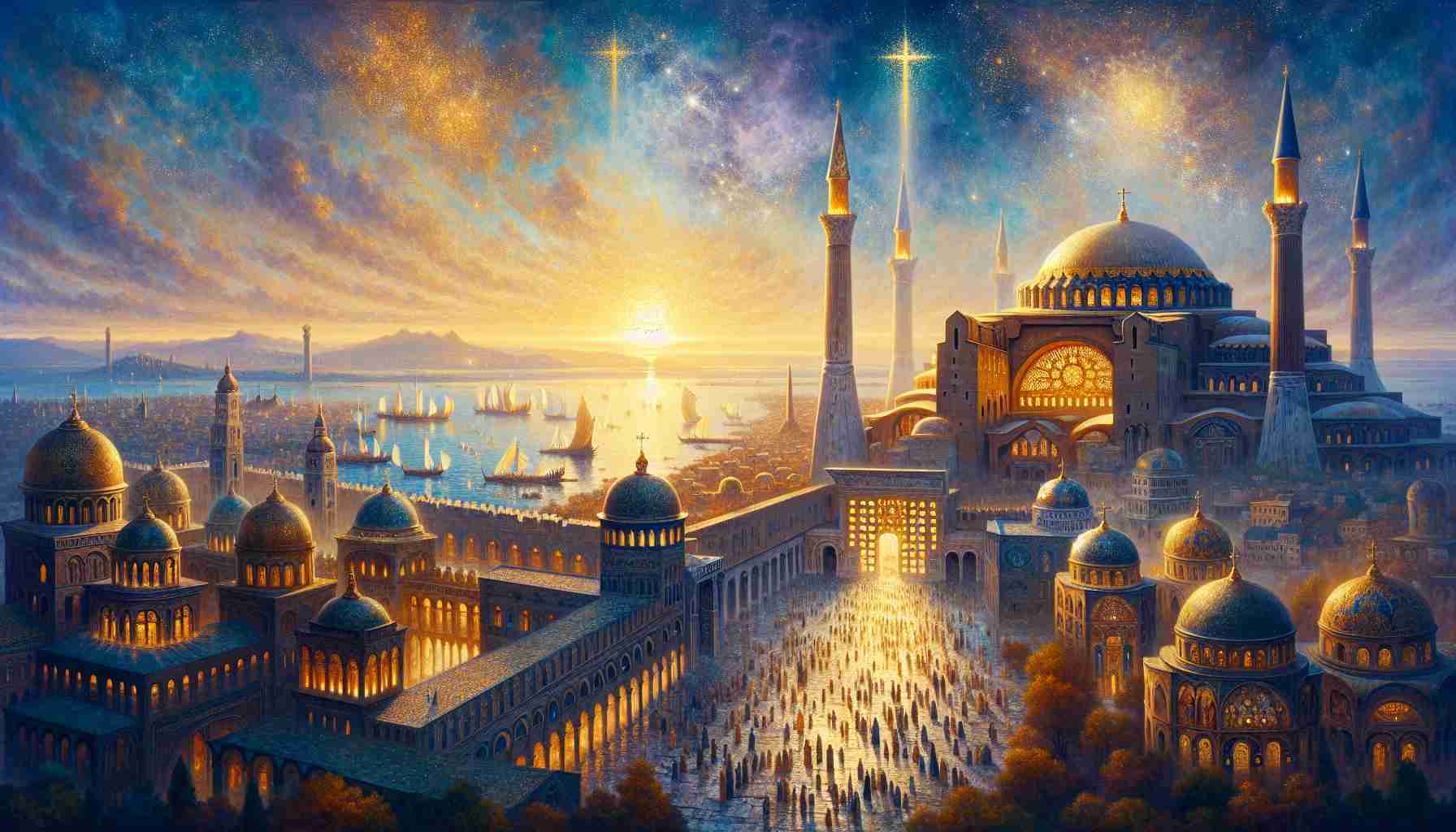

Darkness had long shrouded Byzantium, its narrow streets echoing the age of pagan shrines and dwindling trade. But dawn rose differently on May 11, 330. As incense rose into sea-salted air and banners of purple rippled in the Aegean breeze, an empire bent its knee—not to idols of stone, but to the cross.

The old city, nestled by the Bosporus, no longer bore the name of forgotten emperors. Constantine, Augustus of a once-bitterly divided Rome, had summoned architects, bishops, and armies of masons to shape a vision—etched in marble and faith. He named the city Constantinople. The New Rome. Yet this was no copy of pagan grandeur. It was a city bathed in prophecy.

"Arise, shine," the bishop had read aloud the day before in the Forum of Constantine, his trembling voice rising above the gathered crowd. "For thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee." Isaiah’s words clung to the colonnades and golden domes like morning mist: a blessing, but also a warning. For light, once kindled, cast its shadow.

At the center stood Constantine's own column—a colossal porphyry shaft crowned by a statue of the emperor clothed as Sol Invictus, yet bearing a Christian relic within: a shard of the True Cross. Beneath it, newly anointed bishops whispered of the tension. Old gods, displaced but not destroyed, still lingered in memory. And the emperor, baptized only on his deathbed, straddled two worlds.

But the city pulsed with new conviction. Basilicae sprang like olive shoots across its hills. The boldest of them—a church named Hagia Irene, "Holy Peace"—rose first among them. Its timber roof echoed with the psalms of those who walked away from Martyrdom’s bloodstained arenas, praising not Caesar but Christ. Later, a greater marvel would rise: the Hagia Sophia, its name inscribed even among hostile Persians with awe, as if its dome gathered heaven into brick and vault.

Yet power always tests faith.

Athanasius of Alexandria, exiled thrice for defending Christ's divinity, once walked these halls beneath imperial mosaics. His footsteps stirred political unrest and doctrinal debate, but also courage. In a city that sang Glory to God in the highest with every tolling bell, heresy still whispered behind church doors. The Arian controversy—the question of Christ's nature—fractured bishops, swayed emperors, and nearly tore the city asunder. Architects built for heaven, but believers wrestled in mud.

Some said Constantine had seen a sign—a cross traced in the sky above the Milvian Bridge, with the words in hoc signo vinces—"in this sign, conquer." Others claimed the vision came by dream or by message from a divine and terrible voice. No bishop could prove it. But the Labarum standard had marched with legions since, gold against crimson. It flew now above the city gates, a symbol defiant and fragile.

Pilgrims began to arrive, wide-eyed wanderers from the deserts of Sinai, the shores of Gaul, the riverbanks of Armenia. Their sandals tread on streets paved with stone carved centuries before Christ’s birth, now consecrated by His name. In the Great Palace, where marble lions flanked the throne room and fountains sang in carved courtyards, Constantine presided no longer as son of Mars, but as servant of Christ.

Still, Rome smoldered behind him. The West would fracture—the Goths press, the Vandals howl across Alpine passes. But Constantinople endured, a lantern held high as night fell on the empire. Even as fire would later consume its libraries, even as Crusaders would crack its ribs to steal her heart, she stood. For what Constantine built was more than walls.

He built proclamation.

In the Hippodrome, races thundered beneath imperial galleries, and crowds shouted not only for champions, but for creeds. “Homoousios!” thundered fervent lips. “Christ is of one substance with the Father!” And thus a doctrine forged by councils rang louder than chariot wheels. The city gave faith not just stones to stand upon but breath, echo, defiance.

Time, ever grim, would test her. In 1453, the crescent would rise over her shattered gates as Mehmet's armies surged through her ruins. The Hagia Sophia, dressed in crosses and icons, would echo instead with muezzin’s call. Yet even then—especially then—pilgrims wept not only for what was lost, but for what had been planted.

Constantinople had lit her lamp when the world darkened. And who could say where the light stopped?

For faith, once enthroned in marble domes and sanctified halls, fled with the faithful—over mountains, seas, and generations. Russia, Greece, Armenia, and the distant isles of Britain bore her imprint. Though emperors turned to dust, the gospel walked onward in her name.

And Isaiah’s call, once read beneath bronze skies in her forum, clung still to her legacy: “For thy light is come.”

The city did not merely rise.

It radiated.