The morning mist clung to the marshlands beside the River Borne, veiling the tall reeds like wisps of incense. A light wind stirred the grass, whispering over the thatched rooftops of Dokkum, the pagan holdfast nestled in the wilds of Frisia. On this June day in 754, the land held its breath.

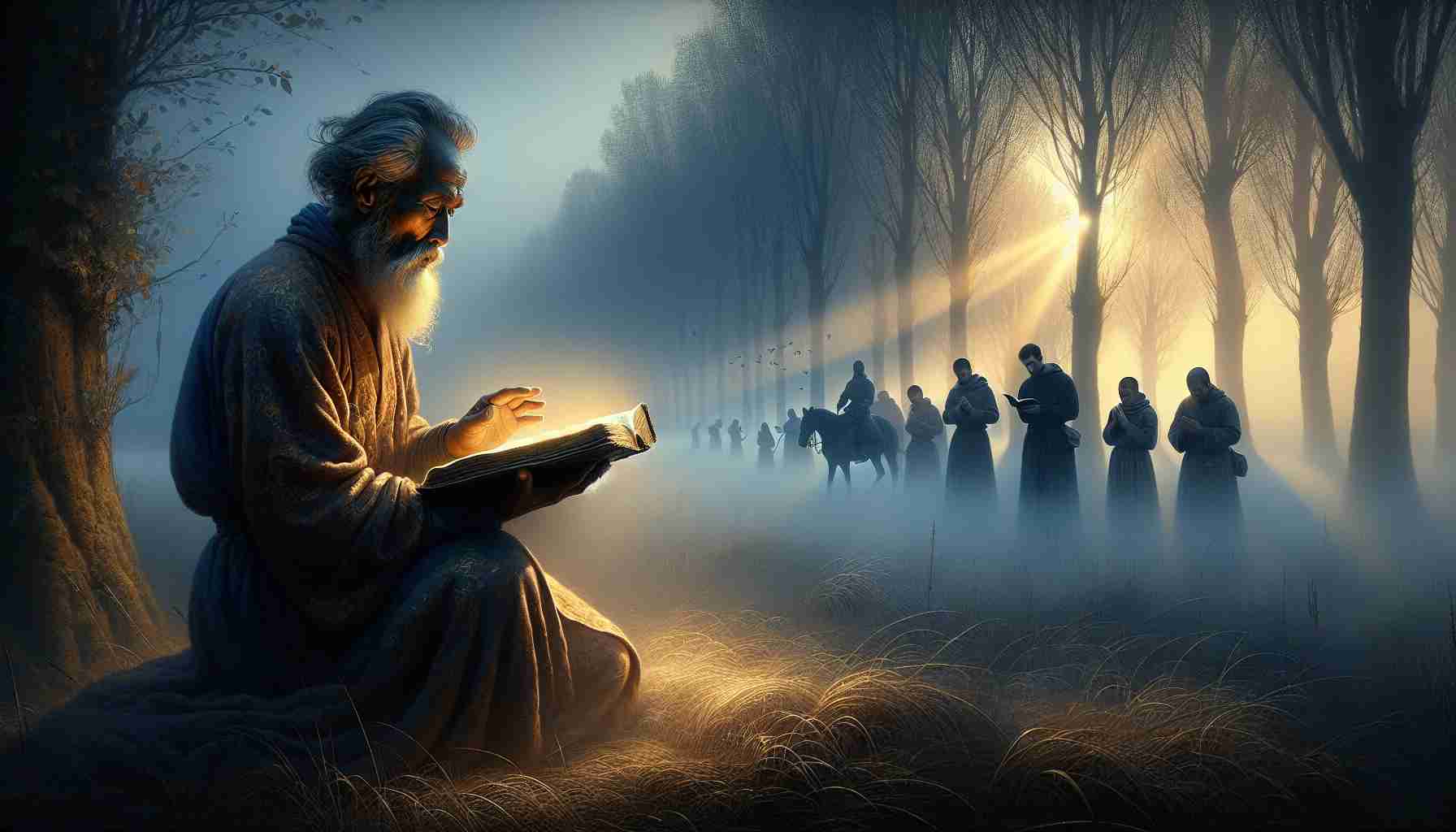

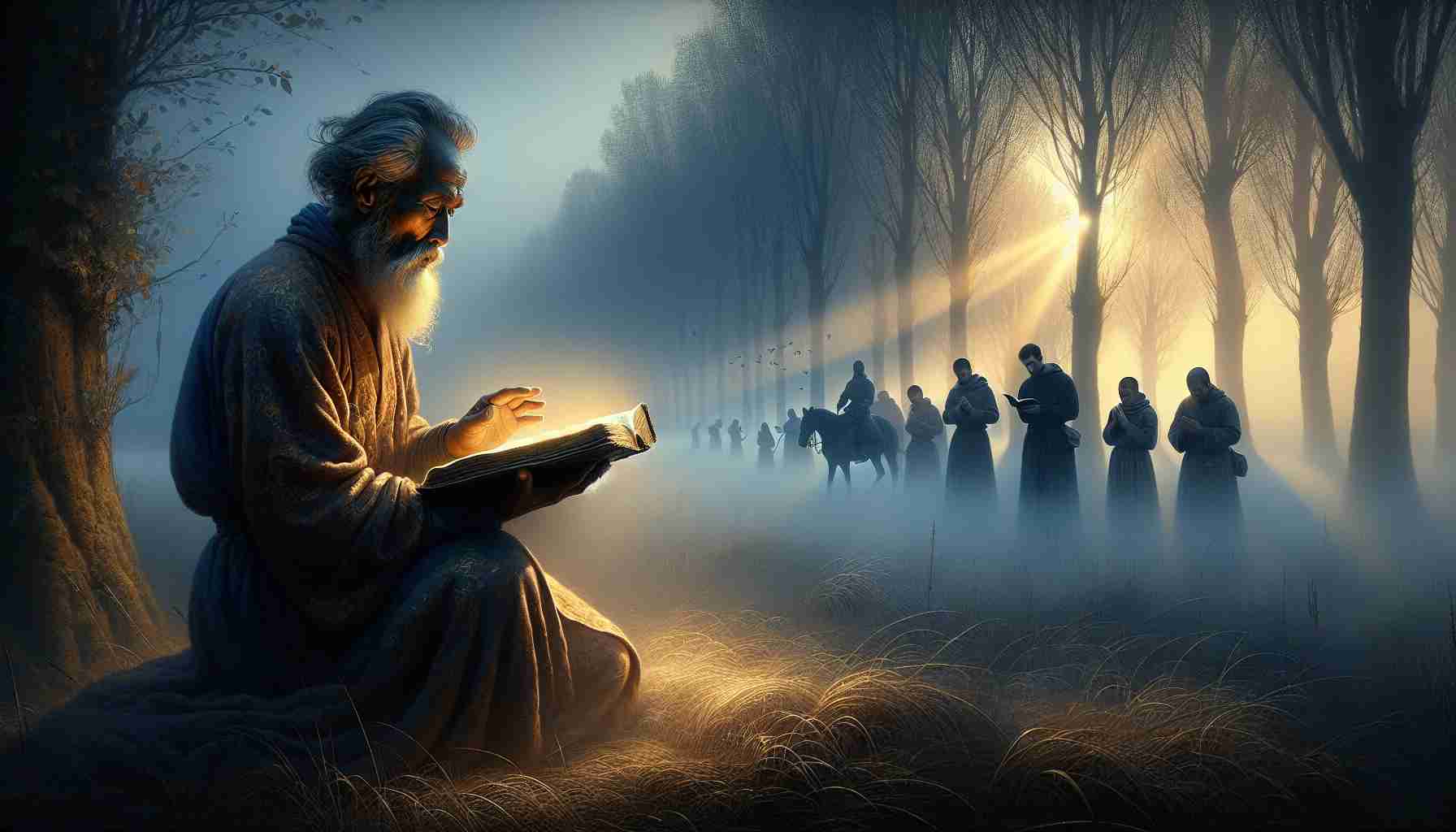

Boniface rose early. At seventy-four, his body ached from the long journey north, yet his spirit burned with a fire no blade could quench. Around him, the younger monks roused from sleep within the rude Christen camp, their voices soft with hymns. A makeshift altar stood on packed earth where dew still sparkled. On it lay a single Book—his Vulgate Bible, worn smooth by decades of travel across forests and courts, abbeys and battlefields.

He had come to Frisia not to escape comfort—it had never known him—but for the souls tangled in Thuner's shadow. These northern tribes still clung to their blood-gods and sacred groves. Yet Boniface had seen idols fall. In Geismar, where Thor’s Oak once towered like a defiant sentinel, he had lifted his axe and felled it before a stunned crowd who watched thunder fail to strike the blasphemer. He had built a church from its timbers.

Now he waited in a clearing for his final sermon. That morning, a local convert had whispered of danger—Frisian warriors on horseback, hidden beyond the tree-line. His young companion, the deacon Eoban, urged retreat. But Boniface refused. “Do not resist them,” he said. “We are called to die, if need be, for the name that saves.”

He opened his Bible again to the worn page. “Whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake and the gospel’s will save it.” The words of Christ in Mark 8:35, inked with a trembling hand under torchlight decades ago. They had followed him from Devon’s cloisters to Bavaria’s dark woods. They followed him now.

The sound came first—hooves and shouting, the cry of steel drawn from scabbards. The monks formed a close circle, shielding the altar, their chants swelling into song. Boniface did not rise. Instead, he knelt, the Gospel still in his hands, and looked upon the grove.

They burst through the trees—thirty at least, wild-haired and painted, blades raised with fury. One monk moved to block their charge, and fell with a cry. Another grabbed a crucifix and raised it high until an axe split the cross and his skull together. Eoban was struck from behind and crumpled at the bishop’s feet.

Amid the chaos, Boniface did not shout or flee. As the first blade descended, he raised his book—not in defense, but in offering. The blow shattered his skull. Blood stained the parchment. The Songs of David ran red.

When the frenzy ended, thirty lay dead, including Boniface and fifty-two of his comrades. The warriors fled with sacks of books and chalices, unaware that they had sown something far stronger than fear.

In that killing field, the Bible from Boniface’s hands remained. Its pages had torn where the sword had struck, yet some letters still pulsed with life. Local Christians returned and retrieved it with reverent hands. Raised prayers. Laid stones.

In time, over Boniface’s resting place in Fulda, a great abbey rose, becoming the sacred heart of Christian Germany. The blood he spilled was not wasted—it baptized a continent. His martyrdom sent shockwaves to Rome, where Pope Stephen II wept and called him not by name, but by title: the Apostle to the Germans.

Centuries later, at that same clearing in Dokkum, children played amid the reeds, unaware their laughter echoed in the ruins of once-holy violence. A small chapel rose nearby, though none could say exactly where the old altar had stood. Pilgrims still came, some in silence, others with songs, drawn not by statues or gold, but by the memory of a man who raised no sword, only Scripture.

And in Fulda’s cathedral, deep within a crypt of stone and incense, his bones rest still—witnesses that when a man chooses the cross over the crown, heaven builds from his ruin.

Because one man knelt instead of ran, a thousand churches would rise.

Because Boniface held the Gospel to his chest and counted the cost—Christendom took root where oak and idol once reigned.

And the words he carried to his grave still echo: To live is Christ. To die is gain.