Dust clung to the sandals of the messenger as he crossed the threshold of Alexandria’s episcopal villa. The sea breeze, usually strong enough to stir the palms lining the courtyard, stifled beneath the weight of grieving silence. Inside, a dim oil lamp flickered before the bed of Athanasius, the fire’s tremulous light dancing across the walls like whispers of final prayers. The bishop, wrapped in his linen robe, breathed no more. May 2, 373. The Father of Orthodoxy had passed into eternity.

Despite his fragile body, death had come late to Athanasius. He had wrestled not with flesh and blood but with emperors and heresies, defending the mystery laid bare in the Gospel: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1). Beneath his quiet expression now rested decades of defiance—five exiles, a dozen coups within the church, and the ire of rulers more interested in peace than truth.

Outside the villa, the citizens of Alexandria murmured. The city was no stranger to unrest—its streets had run with the blood of martyrs and philosophers—but Athanasius had weathered every storm with uncanny resilience. For many, it was impossible to imagine their church without his fierce, burning clarity.

Far to the north, in the imperial court of Constantinople, well-tailored courtiers recalled bitterly how this bishop, mere sand beneath the empire’s boots, had once outmaneuvered emperors. Even the mighty Constantine, who called the Council of Nicaea in 325, had underestimated Athanasius. The council hall, sweltering beneath the Anatolian sun, had echoed with arguments then. Arius, the presbyter from Libya, insisted the Son of God was not eternal—higher than man, yes, but made, not begotten.

Athanasius, then just a deacon, burned in indignation. The Word was not a creature but co-eternal with the Father—never having a beginning, never shaped by time. The opponents smirked at the young man’s vehemence, yet by the council’s end, his logic and flame became doctrine. From Nicaea emerged the Nicene Creed, etched with the words homoousios—“of the same essence.”

But creeds do not guard themselves. After Constantine died, power shifted, and Athanasius became a hunted man. He fled into deserts where monks wrapped in animal skins chanted Psalms without ceasing. In their candle-lit cells, he found brothers who understood the price of loyalty to the Word.

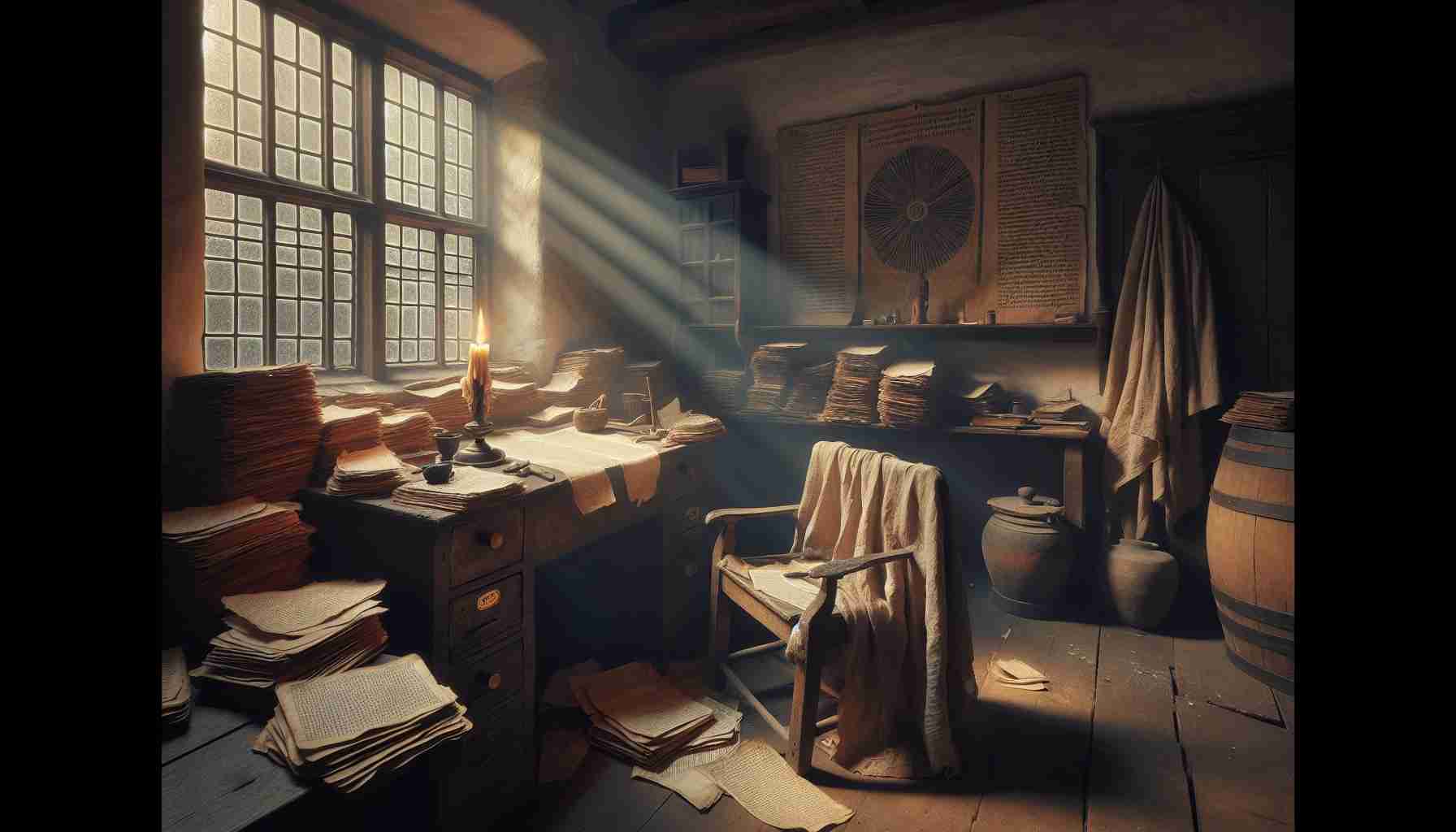

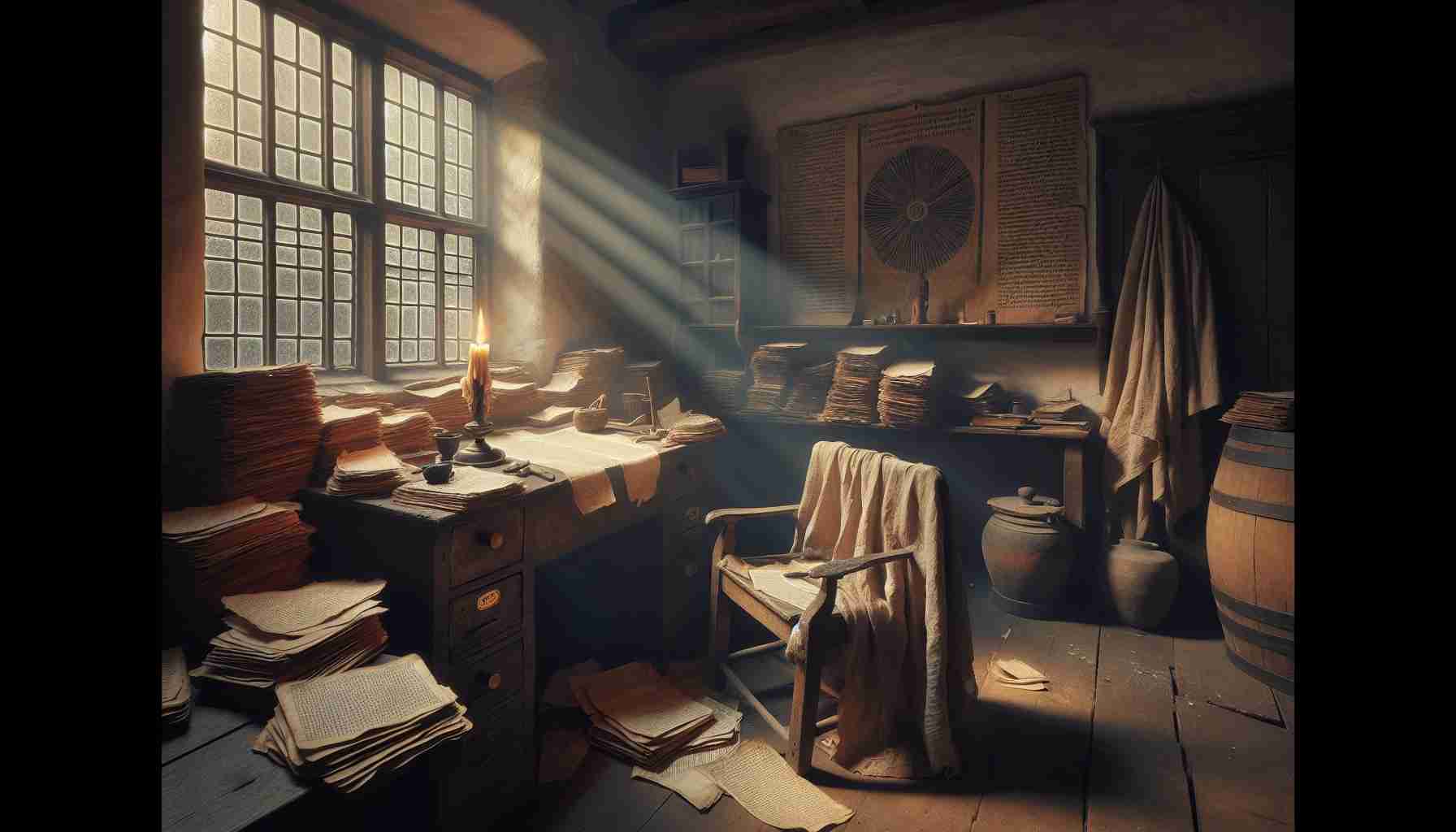

It was said in later years that Athanasius slept with a copy of the Psalter beneath his head and wrote by starlight in exile. During his third banishment, he penned On the Incarnation, a text containing mysteries like bread—simple enough for the poor, rich enough to feed the wise. “God became man that man might become God,” he wrote, brushing parchment beside Nile reeds and moonlight, while imperial guards scoured the region for him.

Alexandria changed while he was away each time. New bishops—backed by heretical factions—briefly filled his seat, tearing down doctrine and committing violence in the name of peace. Yet whenever Athanasius returned, the people rose to greet him with chants, their voices echoing through the colonnades: Athanasius contra mundum—“Athanasius against the world.”

Not that he sought fame. His table was simple—black bread, lentils, date wine. The walls of his library collapsed under scrolls, many penned in his own hand, warning that heresy wears the nation’s seal and whispers lies in the language of compromise. Orthodoxy was not convenience. Truth was a cross—a weight to be carried through injustice while trusting God to vindicate in His own time.

In one exile, Athanasius helped preserve the desert teachings of Saint Antony, the hermit who wove baskets by hand and spoke to demons like spoiled children. “The time is coming when men will go mad,” Antony once said to him, “and when they see someone who is not mad, they will attack him, saying, ‘You are mad—you are not like us.’” Athanasius recorded it faithfully and watched the prophecy bloom in his own life.

Now Alexandria stood quiet before the tomb being carved near the Basilica of Theonas. Metal rang out as stonemasons shaped marble, while boys read from John’s Gospel nearby, their voices brittle in the sea wind. “All things were made through Him,” one of them read, hesitating over the Greek, “and without Him was not any thing made that was made.”

Word spread across the coastal cities—Carthage, Antioch, Rome—that Athanasius was gone. But the Creed remained. The writings remained. And the Church, once shaken by Arius’s song, now stood enclosed in the walls he helped build with blood and ink.

In centuries to come, children would be baptized with the same words he defended. Discord would return, emperors would rise and fall—but the Word, once debated in Arian councils, would not diminish. It had been defended by a man who wore exile as a crown and truth as armor.

Outside his tomb, under Alexandria’s stars, censer smoke rose into the dark, mingling incense with the sea air. One of the deacons folded a final robe over the body and whispered a blessing.

In the beginning was the Word.

And the Word endured.