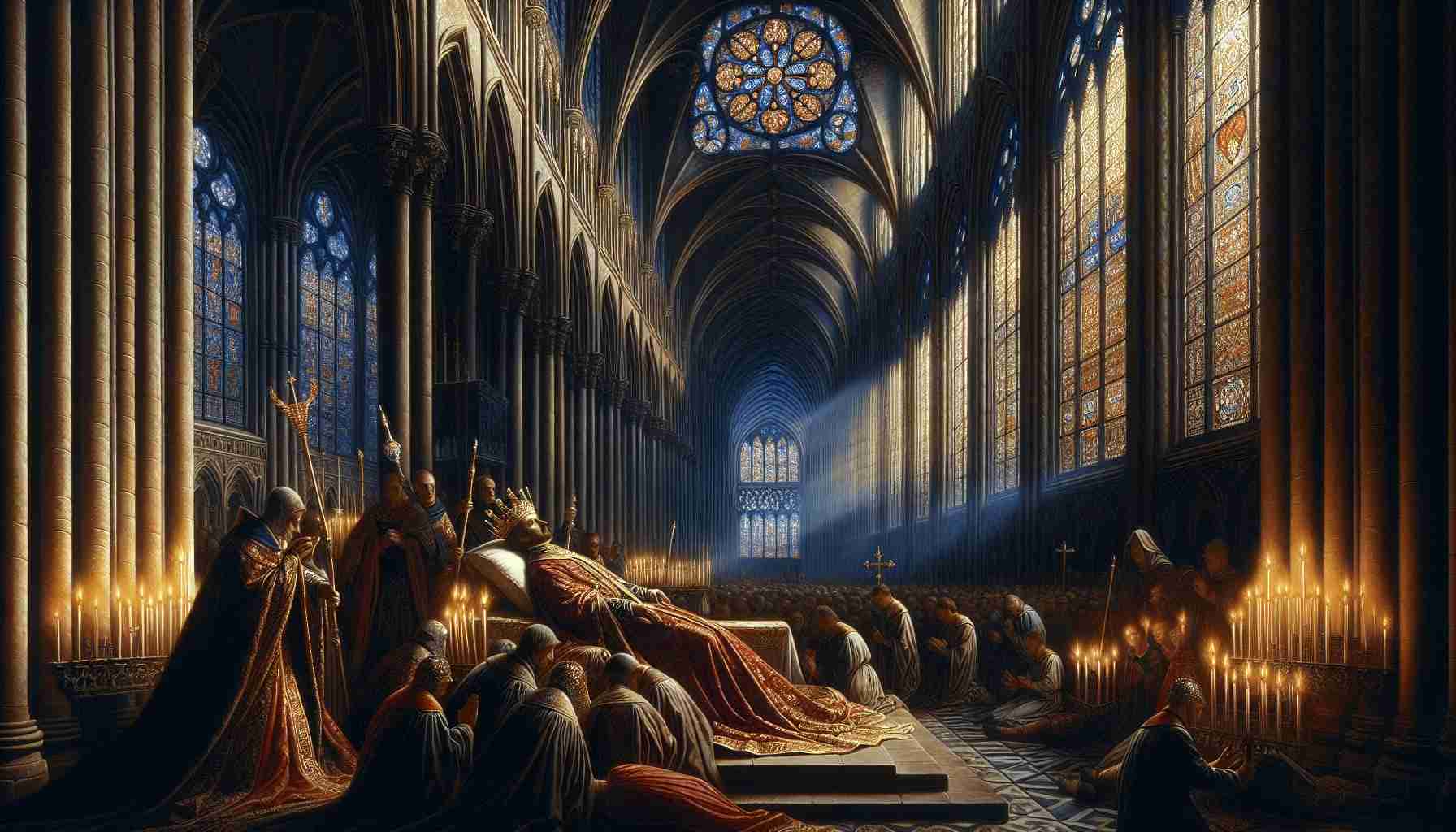

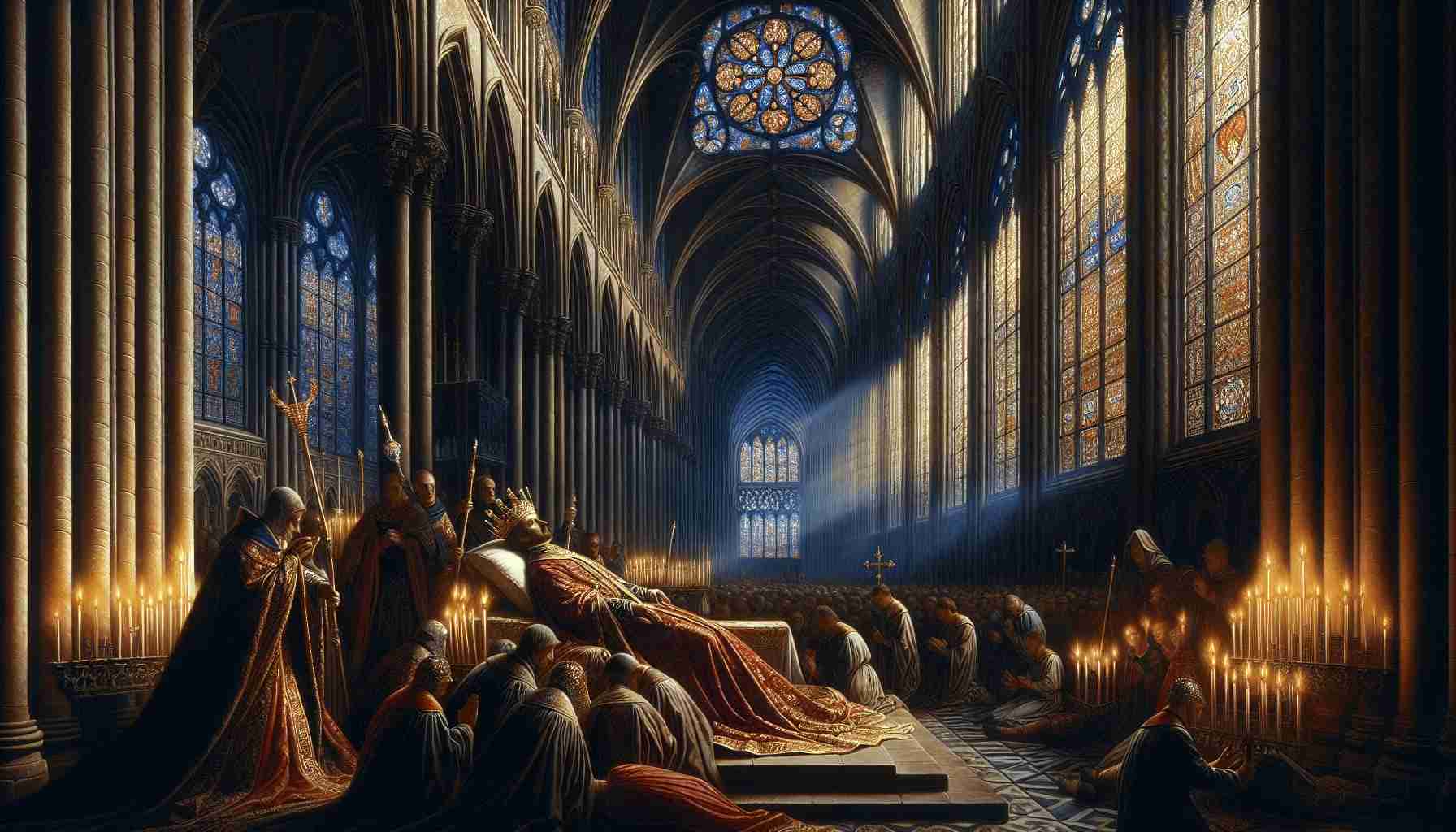

The bells of Westminster Abbey tolled heavy over the city. June 21st, 1377—London held its breath. Inside the abbey’s great heart of stone and shadowed glory, priests chanted psalms in Latin while incense thickened the air like fog on the Thames. Beneath the vaulted ceiling, King Edward III lay still, his robes of gold and crimson dimmed by candlelight, his scepter resting across faded hands.

It was the end of an era—fifty years of reign, threaded through war and worship. England bowed not only to a monarch but to a man who had made faith his fortress and the cross his compass.

Outside, across the worn cobbles of the abbey’s courtyard, commoners clutched rosaries and whispered prayers. Many remembered Edward not merely as king, but as guardian of the realm’s soul. His coin had rebuilt crumbling chapels, his name had graced chantries and shrines. From candlelit altars in Yorkshire to the sons of noblemen knighted into his Order of the Garter, Edward’s hand had shaped a Christian kingdom.

Yet heaven’s will was not always gentle.

The old king's eyes had once been sharp with vision. When he claimed the French throne in 1337, many saw it as ambition—but Edward wove his cause in divine justice. Clergy across England echoed his call from the pulpits, dressing the Hundred Years’ War as a sacred duty against tyranny, blessed by Rome and washed in psalms. He rode to war with a crucifix beneath his armor and knights sworn to defend not only crown, but Christendom.

Still, war bred ghosts. The long campaigns left villages fatherless; pestilence crept through the gaps war carved open. The Black Death had gutted England in the 1340s, filling plague pits while church bells rang not for weddings but the dead. Even in Camelot-like Windsor, where Edward founded the Order of the Garter beneath the shadow of St. George’s chapel, nuns whispered prayers for fallen youth as young as fifteen.

Yet the king did not waver. His chaplains murmured Proverbs 21:1 as he met with ministers in his later years: “The king's heart is in the hand of the LORD, as the rivers of water: He turneth it whithersoever He will.” Edward spoke often of rivers—how God guided men's reigns as softly, or as forcefully, as streams split stone. It was not for kings to argue the current, but to correct their course by it.

By the time Edward stood aged and bowed in Westminster’s chapter house, the sickness had begun to steal his strength. His beloved Queen Philippa had died nearly a decade before. More than one son had fallen to death or disgrace. The treasury bore the wounds of prolonged war; the court grew fat with rivalries.

In his final weeks, Edward called for the Book of Hours daily. His nurses watched him trace trembling fingers across thin parchment, following the Magnificat and Psalms, his breath catching most often on words of mercy.

On midsummer’s eve, the abbey’s whispered liturgies grew somber. As the king’s life slipped away, a storm rolled across the city, brushing the Belfry and Tower with wind and thunder. Some said an angel was seen at the cloisters. Others claimed the old white hart—Edward’s heraldic emblem—roamed through Richmond fields that night, vanishing at first light.

He was buried not far from the high altar, amid stone effigies of kings before him. Around his tomb, stained glass flickered gold and royal blue—the colors of the Virgin and of battle. The Order of the Garter knights gathered in mourning attire, bearing their jeweled badges: “Honi soit qui mal y pense.” Evil to him who thinks evil of it—a chivalric motto, yet also a prayer of vindication.

In distant churches funded by Edward’s conscience, monks spoke of his piety while questioning his war. In Canterbury, voices rose in elegy; in Avignon, the papal court weighed the succession. But in the silence of the abbey, the story whispered a deeper truth.

God had shaped a king—not flawless, not unbloodied—but sovereign by grace. Edward had governed in the shadow of cathedrals and beneath the symbol of Christ crucified. His court, flavoured with liturgy and lance, had left England changed.

And as the sun split the clouds on the morning after his death, gilding the buttresses of Westminster one more time, a young boy—his grandson Richard—was led up the steps of the coronation throne. Anointing oil was prepared by the abbey monks. The weight of the crown rested once more in clerical hands.

In the echo of Edward’s rule, another truth endured—the heart of the king is in the hands of the Lord. And so is the fate of every kingdom, and every soul.

Dust returned to dust, but legacy stands in stone.