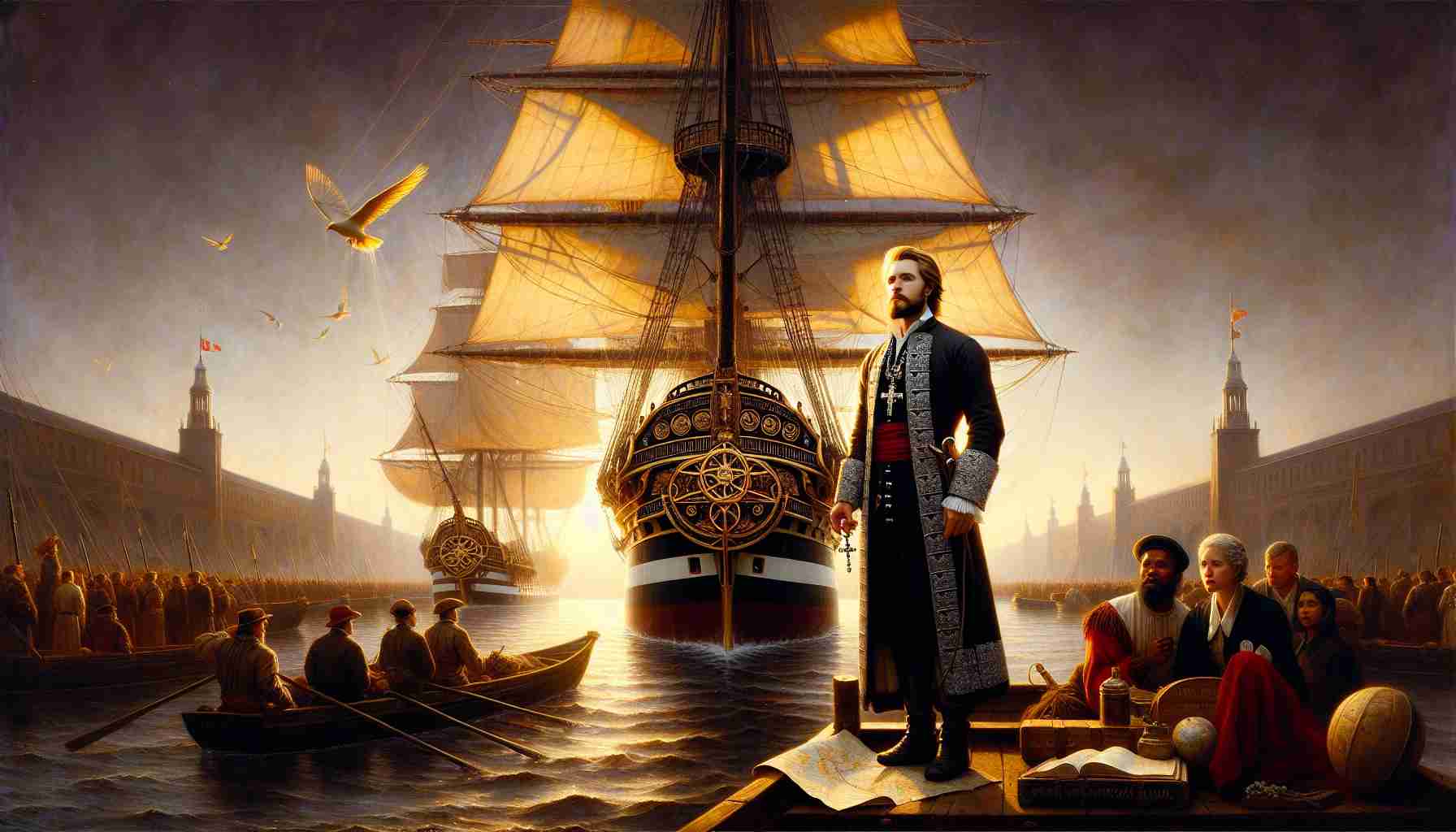

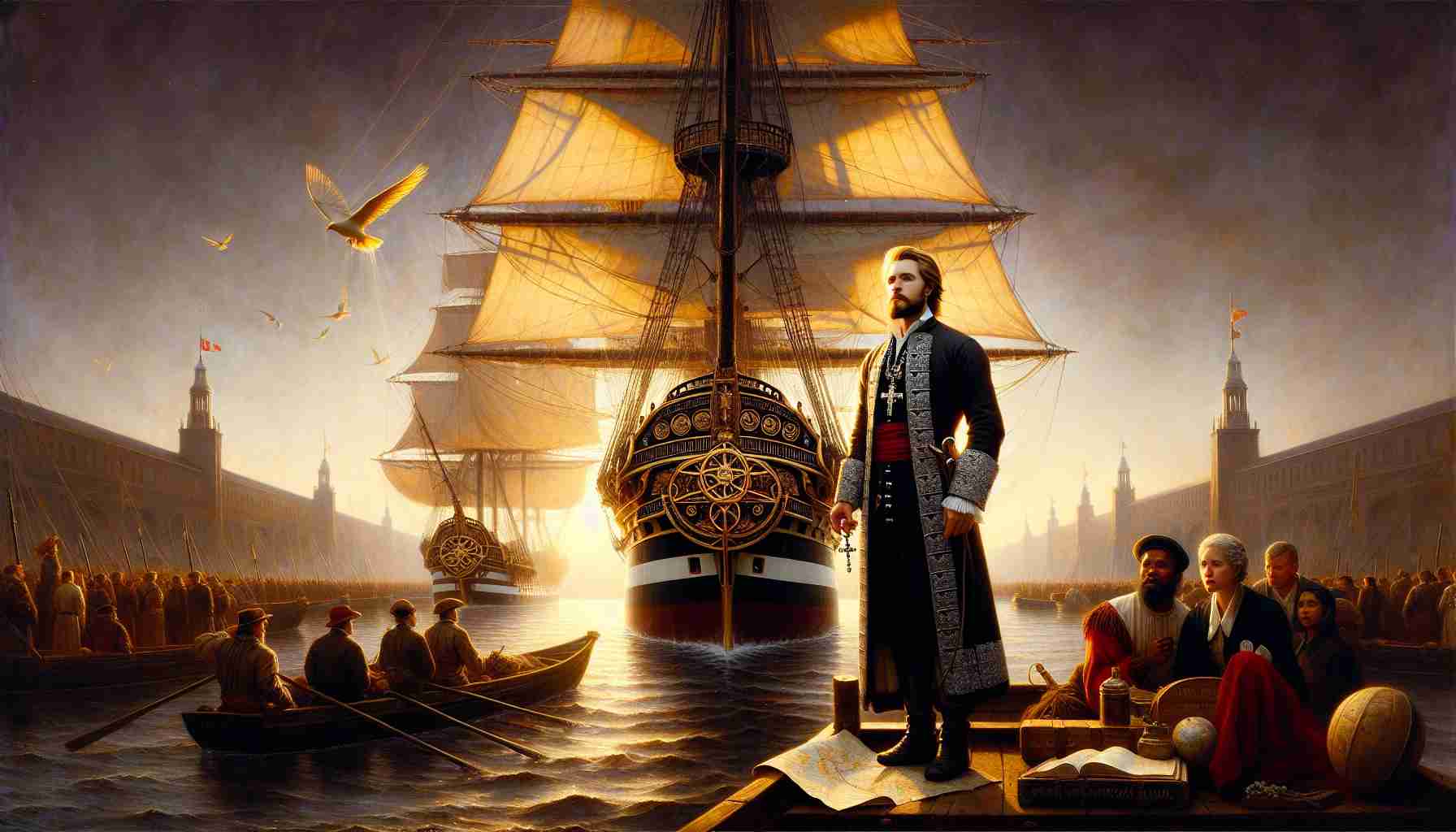

The sun rose slowly over the River Tagus, casting golden light on the bustling harbor of Lisbon. Wooden masts groaned as crews loaded casks of water, dried meat, and sacks of spices from Africa’s coasts. Among the ships preparing to depart, one stood loftier, her carved stern shimmering with the emblems of Portugal: the armillary sphere of celestial navigation, and above it, a lacquered wooden cross—the Cruz da Ordem de Cristo—bright with red, defiant against sea winds.

On July 8, 1497, Dom Vasco da Gama, son of Estêvão da Gama, took the helm of this crowned flagship. He stood clad in a black doublet trimmed with silver thread, fingers fiddling with the rosary beneath his cloak. The coil of years had led to this moment: Portugal’s dream of reaching India without crawling around hostile Ottoman lands or relying on Venetian traders who controlled the spice markets.

King Manuel I, sworn protector of the faith, had ordered it: not merely a voyage for wealth, but a declaration of spiritual ambition. Alongside navigators, cartographers, and cannon crews, boarded Franciscan friars and interpreters, men of letters and prayers, bearing Latin breviaries and polished chalices. A cross in every hull, a crucifix in every heart.

"Go therefore and make disciples of all nations..." The words of Christ, etched into da Gama’s private psalter, burned in his thoughts (Matthew 28:19). This was no conquest—it was commission.

Weeks turned to months. The Atlantic yielded to the uncharted Atlantic-Hind Ocean passage. They rounded the Cape of Good Hope in harsh gales, their sails torn, bodies battered, many sickened by scurvy. At Malindi, on the East African coast, they found a guide—an experienced Arab pilot likely versed in Ptolemaic maps—who brought them through monsoon winds toward the fabled land.

In May of 1498, da Gama finally anchored off Calicut, Kerala—a coast dense with palms and humming with incense-trade and textile bazaars. The scent of clove and cardamom was thick in the air. Here was India, but it did not kneel.

The Zamorin of Calicut, robed in saffron silk, sat amid carved sandalwood walls. Gold earrings dangled beside his cheekbones as Vasco da Gama approached offering gifts: beads, cloth, coral. It was a moment meant to open paths for diplomacy—and evangelism. But the court, rich beyond the trinkets of Lisbon, smirked at such foreign offerings.

Vasco da Gama stood silent, yet in his satchel, beneath the cargo manifest and trade charters, he carried the blazing symbol of his mission: a painted image of Christ crucified, flanked by the Virgin and St. Francis of Assisi. Though the Zamorin displayed quiet tolerance, the seeds of spiritual tension were planted, seeds that would blossom into both missionary work and bitter conflict.

Still, the Portuguese left their mark. Chapels soon dotted the Malabar coast in later decades, built of lime and coral stone. Churches dedicated to St. Thomas and St. Francis Xavier rose among fishing villages, where names like João and Miguel emerged among local converts. The voyage had stirred awakening.

Yet, da Gama's path would not always be righteous.

Years later, on his second voyage, embittered by resistance and driven by zeal without temperance, he ordered acts that appalled even his own men. When locals rejected the Portuguese terms, he sanctioned the plundering of ships—especially Muslim ones—actions justified then by the politics of empire and the call to defend the faith.

In 1502, off the coast near Cochin, one merchant ship—laden with pilgrims returning from Mecca—was seized and burned, its hundreds of passengers stranded or slain in oily water. Some chroniclers later whispered that da Gama wept alone in his chamber that night, clutching his crucifix. Others wrote that he slept soundly beneath the flag of the Order of Christ.

Faith had launched the ships—yes—but ambition, fear, and power now vied with that holy fervor.

And yet, from that same coast, from the sunbaked land where pepper vines clung to red clay walls, monks preached the words of the Gospel beneath coconut palms. Thomas Christians, whose ancestry purported links back to the apostle who doubted and then believed, welcomed new brethren as churches merged East and West. Over generations, baptisms surged. The liturgy adapted to language and culture, while stone baptismal fonts bore both Latin and Malayalam inscriptions.

The cross had not arrived unbroken, nor without infliction—but it had arrived. Vasco da Gama’s journey carved more than trade routes; it carved witness.

In 1524, aged and weary, da Gama returned to India, this time as Viceroy. Fever consumed him in Cochin, and he died on Christmas Eve. His body, once buried beneath the kerala soil, was later returned to Portugal, laid to rest in the Jerónimos Monastery—a chapel funded, in part, by the profits of India and adorned with carvings of seaweed, lions, and angels.

His life remains an uneasy legacy. Hero to some, oppressor to others, evangelist and admiral both. Yet in the wash of history, one truth persists, gentle as a tide: a man heard Christ’s call to “go”—through waters dark and bright—and went. And the world, for better or worse, was never the same.