The bells of Hagia Sophia rang with desperation on the last day of Constantinople. May 29, 1453 — the day the Christian city fell.

Throughout the broken walls and bloodied streets, cries shattered the air like shattered mosaics, once formed in devotion, now ground beneath foreign boots. It was the end of the Roman Empire — not the pagan version born in wolves and myth, but the Christian continuation built by Constantine and baptized in flame. For over a thousand years, this city stood — queen of cities, throne of emperors, center of Christendom in the East.

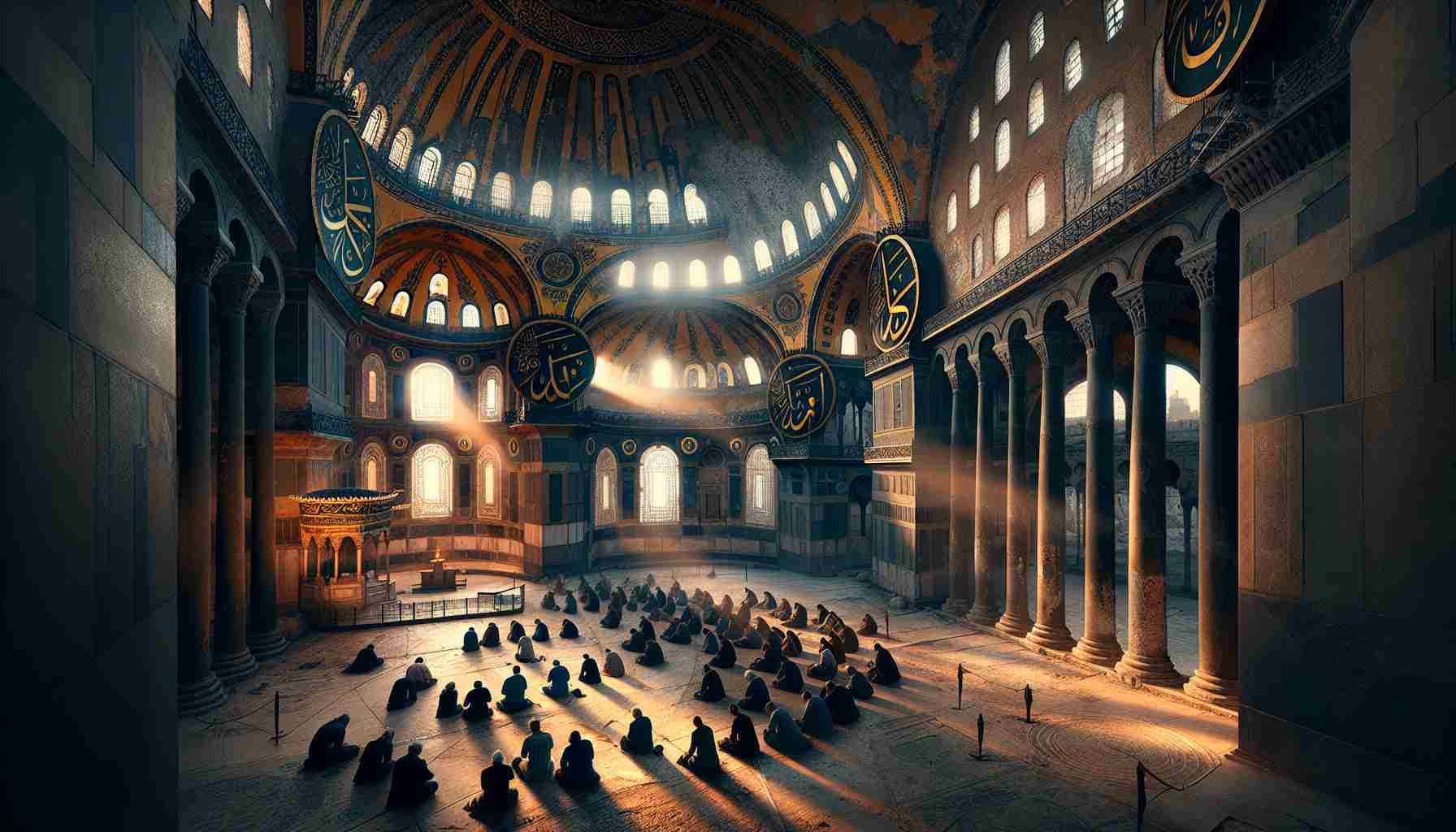

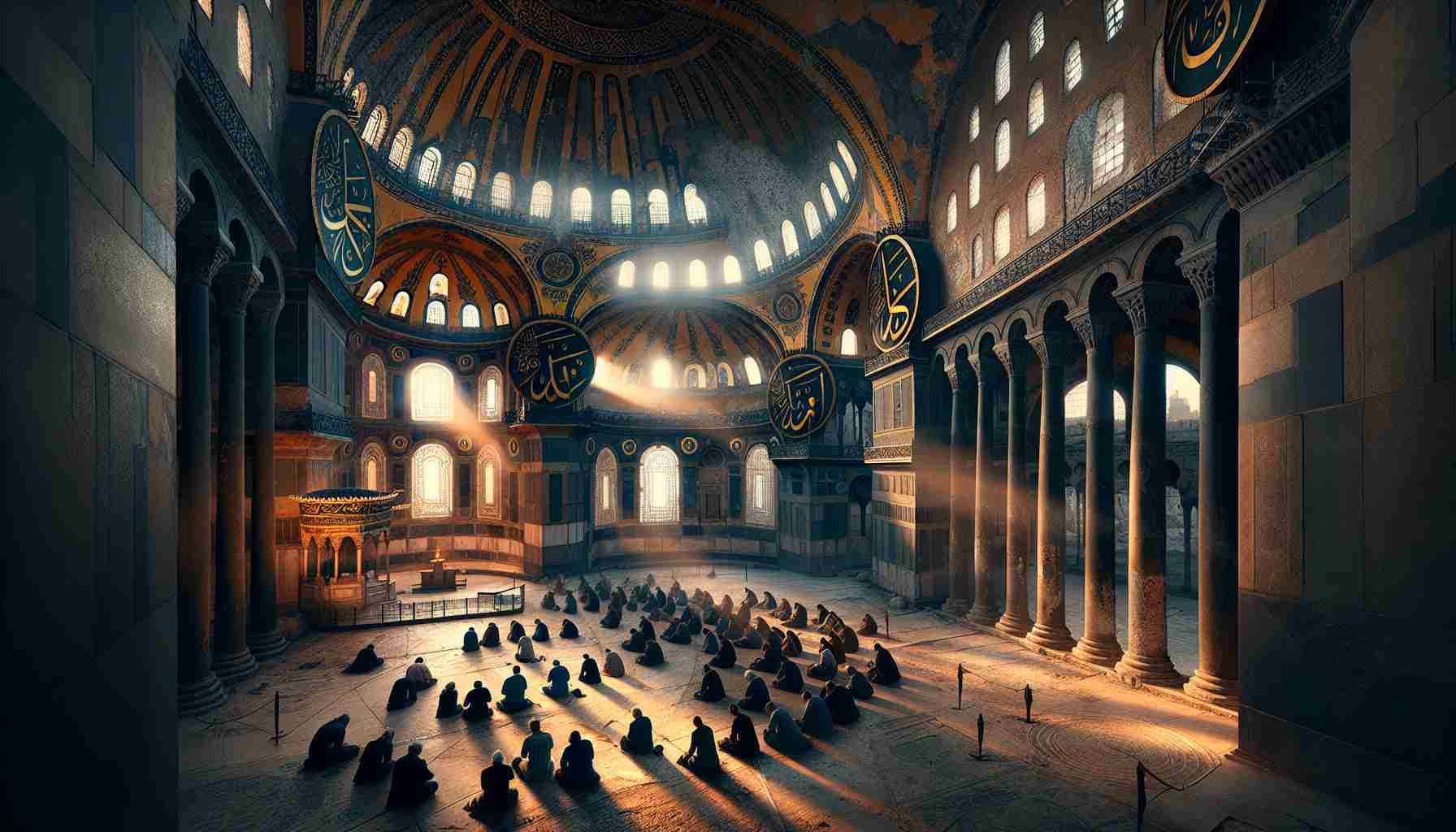

Beneath the great dome of Hagia Sophia, priests gathered, cloaked in incense and fear. The sanctuary still bore golden seraphim staring from lofty corners, and remnants of sacred chants clung to the massive columns like whispers of angels. The mosaics above the apse — Christ Pantocrator, Mary Theotokos — watched over the chaos with silent endurance.

People had come in waves, seeking refuge. Refuge not just from sword, fire, and cannon, but from despair. There, under the ochre light filtered through ancient windows, Latin and Greek, noble and beggar, clergy and soldier knelt shoulder to shoulder. Once divided by schism, now united in a final liturgy.

“Through the LORD’s mercies we are not consumed, because His compassions fail not. They are new every morning,” the priest intoned, his voice trembling as he recited from Lamentations. “Great is Your faithfulness.”

Some sobbed openly. Others whispered words their ancestors taught them. Faith endured — not in the strength of walls or rulers, but in the mercy that outlives kingdoms.

Outside, Sultan Mehmed II surveyed the trembling skyline. His cannons had torn a path through once-unshakable defenses. He was twenty-one — ambitious, brilliant, and hungry for empire. But even he paused before Hagia Sophia’s doors, awed by the immensity of its dome, the grandeur of what man had offered God.

“They said heaven touched earth here,” an elder janissary murmured.

“And now heaven yields,” the boy sultan replied, but his eyes did not mock. He ordered the building converted to a mosque. The mosaics were plastered over, not destroyed, hidden beneath veils of Ottoman ornament. Somehow, the eyes of Christ remained, watching from beneath the paint, as if God was not so easily erased.

But the story did not end within stone walls.

Far off, on green coasts of the far North, disciples of a man long dead still sailed under Christ’s banner. Saint Brendan the Navigator, an Irish monk of the sixth century, had once pursued the Promised Land of the Saints — a distant shore untouched by sin. Some believed he reached Iceland, maybe even the Americas. Others believed his voyage symbolic — faith braving the uncharted deep.

Brendan had died centuries earlier on May 28, 585, the day before Constantinople’s fall long in the future. But his legacy drifted like a quiet flame through the heart of Celtic Christianity. Churches rose across stone-flecked isles in his name. His quest embodied what the fall of a city could not destroy — the belief that God leads, even through loss and horizon.

A monk in Iona, upon hearing of Constantinople’s fall decades later, copied Brendan’s tales into worn parchment. “The Church is not walls,” he wrote in the margin. “She is the wind in the sails, the prayer in ruin, the fire that refuses ash.”

In time, the West would rally. Rome would endure. Refugees from Constantinople would bring their learning, texts, and theology to Italy, helping light the Renaissance. The seed of a fallen city would blossom in another time, another tongue.

But on that day — stained with blood and silence — it seemed that Christendom cracked.

And yet.

In the darkened nave of Hagia Sophia, a candle still burned — lit before the doors were breached, set by trembling hands before the altar. It flickered as shadows poured in. And though its flame danced low, it did not die.

Because mercy was not in the marble.

It was new every morning.